Creator Notes #7: Making Money

It doesn’t get any easier

Today, my first attempt at crowdfunding concludes. It has not been a success.

In Creator Notes #6: The Ghosts of Futures Past, I walked through some of the recent developments in the film and television business and how the economic environment has sharpened against independent creatives:

What does this mean for independents and creatives? I’m afraid that there are reasons to be concerned. Experience shows us that consolidation produces cartels which quickly seek to dominate their industries. Independents are often faced with a choice between abandoning meaningful autonomy, and going to work for the cartel, or remaining independent but struggling to make a living.

We have a new film coming out later this year, which ran into a bit of a funding gap during post-production, and in that insoluble quest for “meaningful autonomy”, I thought it would be worth giving crowdfunding a go. I am a big believer in trying new things, and I also hold that failure is a pre-requisite for success, one shouldn’t fear failure or recriminate too hard when it attends. So, full of hope, we launched a Kickstarter that has been running for the past month.

Our project was ideal for the type of niche audiences and subcultures that enthuse on crowdfunding platforms and online communities - we had a number of Big Names attached, all of whom came with their own followings; the funding goal was modest-ish; there was a decent array of sparkly exclusives on offer.

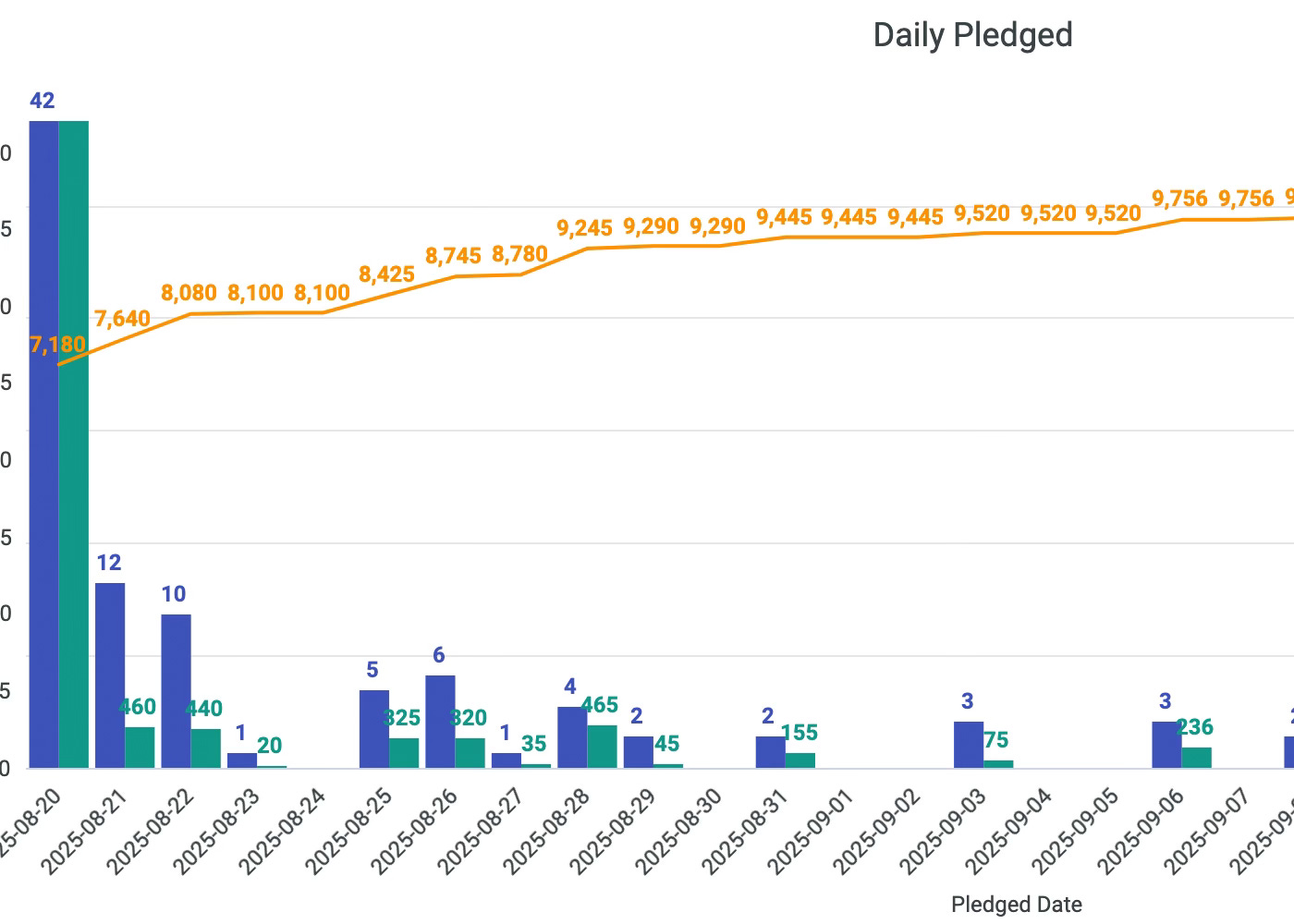

The campaign soared out over the cliffs, hitting 10%, then 20%, then 30% of our funding goal within the first 24hrs, before climbing too close to the sun and plummeting back down towards the black ocean waters, beneath which it remains submerged; the tide will not offer up any limited-edition Blu-Rays with exclusive artwork after all.

One of the themes that I picked up in Creator Notes #6, is that the range of projects that are economically viable has narrowed considerably across recent years:

I worried that [YouTube & streaming] would incentivise a race to the bottom, that it would make anything that didn’t pander to the maximum possible numbers uneconomic and unviable and that artists who produced creative, intelligent, difficult or niche work for a naturally limited audience would be reduced to hobbyists. And I worried that the film business would become a sub-branch of the tech sector.

Over the past decade there has been an industry-wide effort to crowd into a contracting space, my company has been repetitively warned by sales agents everywhere to abandon our deranged adherence to arts, history and culture documentary and go all-in on reality tv, true crime, extreme weather, sharks and Nazis. And a tv industry Nuremberg subsequently executed the Nazis from that list (we did a couple of Nazi shows, including a true crime/Nazi crossover as, obviously, the Nazis were also true crime).

While all this reality tv wisdom was being dispensed, my distressed mind would often turn to the question of what had happened to our audience, the arts & culture audience upon which we had built a thriving business during the Golden Age of physical media. I reasoned (and still do reason) that it must still be out there, but that it’s probably too niche to sustain us in the streaming era, unless we want to be hobbyists, or go to work in the mines on behalf of the entertainment industry cartel.

I had hoped that crowdfunding would offer a viable route back to that audience: it seemed to serve niche interests and communities, and it looked like physical media still had a pulse on Kickstarter, which might help make sense of the money.

We poured effort into it. We produced videos and artwork, launched a website and socials, sent press releases, ran ad campaigns, made podcast appearances, attended conferences; we drove thousands of people to the Kickstarter page, all of whom were loudly enthusiastic about the film. But only a couple of hundred were prepared to part with any money, proving the old adage about drawing a horse to water.

So, why hasn’t it worked? I’ve taken a few useful lessons from the experience. The first is to appreciate what crowdfunding is, and what motivates online communities. For our campaign we worked with an acquaintance who had successfully funded a number of documentary projects on Kickstarter, and he cured me of a misapprehension: people do not want to fund your film, they want to buy and collect rewards. In this formal sense, crowdfunding is better understood as ecommerce, rather than fundraising. You have to work out a retail offer ahead of time, and design your project around that; arriving late in the day and working backwards, as we did, is unwise.

The second lesson is that the landing zone for making a professional living in the creative arts remains narrow and obscure, no matter the medium. It could be that we have been unable to match the right film with a paying audience. The click-through rates from our social media ads were remarkably high – up to 10% on the best performers – but the expectation that films are something that stream for free, or as part of a pre-existing, cheap subscription service, remains stubborn; I noted comments online in which our audience expressed confusion as to why the film wouldn’t simply be instantly available on streaming, without all this eccentric talk of Blu-ray and crowdfunding.

Third, the corpus of physical media is probably in the advanced stages of putrefaction at this point. I don’t think one can run sustainable business off the collectors’ market and, if it were possible to do so, I think it would most likely be with a collectible of something which has some brand recognition, rather than a new documentary release.

Which brings me to a final observation: the projects that appeared to be most successful on Kickstarter were run by people who have pre-existing name/brand recognition, or which offer a product specifically designed to appeal to the closed-system of “people who pay for things on Kickstarter”.

This phenomenon is part of the scourge of the digital era: music streaming works fantastically well for Beyoncé, but any new artist better make sure that they have two full-time jobs alongside their Spotify creator account. And we see it here on Substack, where the most successful newsletters are generally A) Authors, journalists and personalities with name recognition and a pre-existing following or B) People who publish newsletters on the subject of how to have successful newsletters, aimed at the closed-system of people who aspire to publish successful Substack newsletters (the Being John Malkovich principle, which also applies on YouTube and every other platform).

I don’t think that crowdfunding is the answer to the problem of how to produce economically viable, independent films. Could it be part of the answer? Maybe. But I think that would take a carefully chosen project, which is designed around a Kickstarter campaign from its inception. I’d like to give it another go with something, perhaps not a film.

The quest for a hospitable path through the chaos and diminishing returns of the streaming era continues.