Techno-Fascism Part#2: All Too Human

What are computers for? A study in ideology.

What are computers for? This is not a question that had ever really troubled me. As I suspect is the case for most of my generation, computers simply insinuated themselves into my life, at first as a fairly limited way in which to play electronic games in flickering black-and-green, latterly as a small hand-held device, masquerading as a “phone”, that tyrannises every aspect of our existence.

There are, of course, people who think intensively about what computers are for (perhaps some of you are reading this), and those that asked this question early enough in the genealogy of computing had some additional questions to confront: what could computers be for? What will computers be for in the future? And although those questions might continually present themselves to technologists and computer scientists, by now the basic premises of the technology have already been set, there is a history, the horse has bolted and is running amok through our societies, foaming at the mouth and distributing lies, conspiracy theories, espionage, addiction, organised crime and unregulated pornography in all directions.

But in the early days of computing, those technologists were more or less staring at a tabula rasa; the future had to be imagined, and where imagination is put to work, it is quite often under the supervision of ideology.

The First Computers

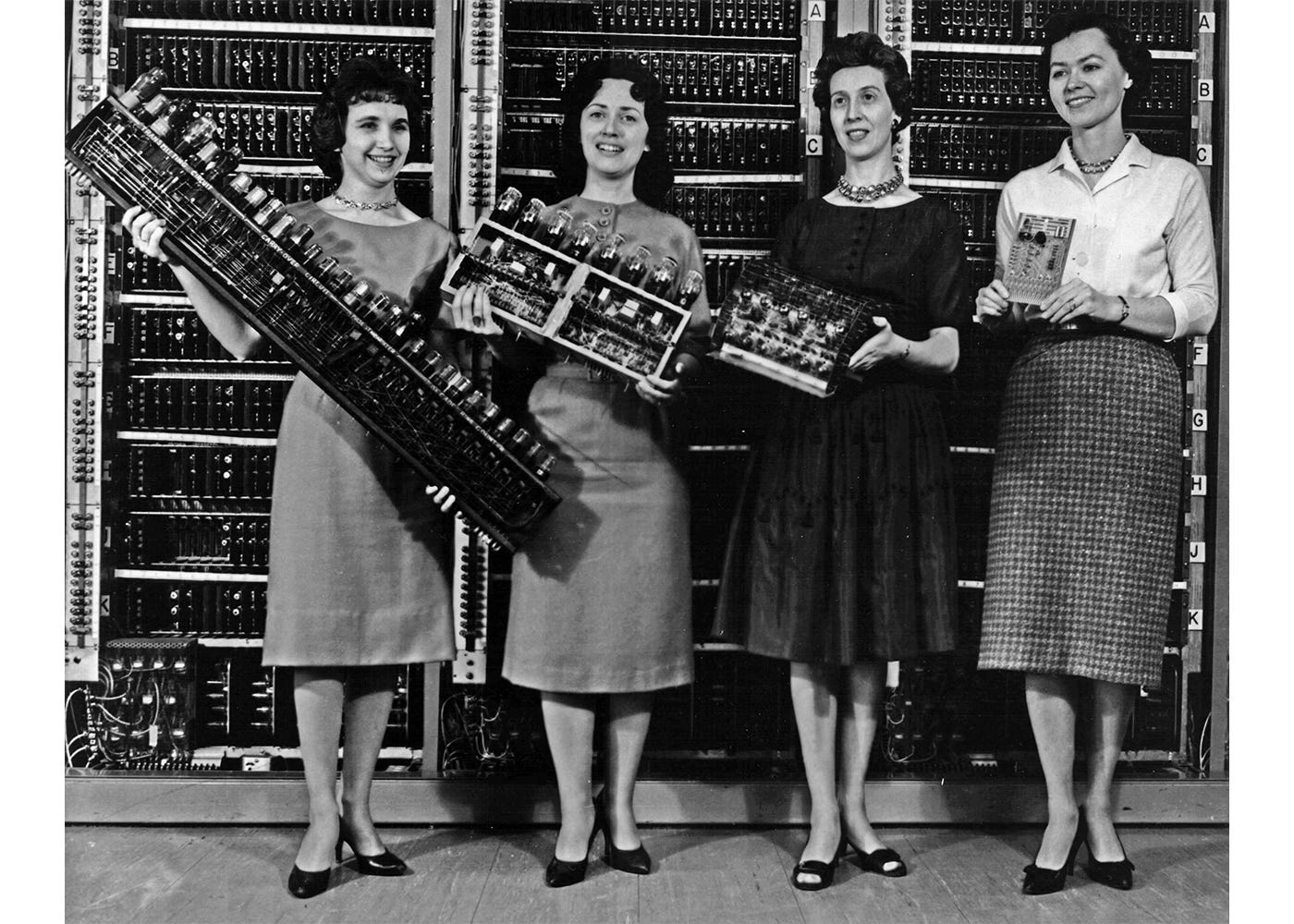

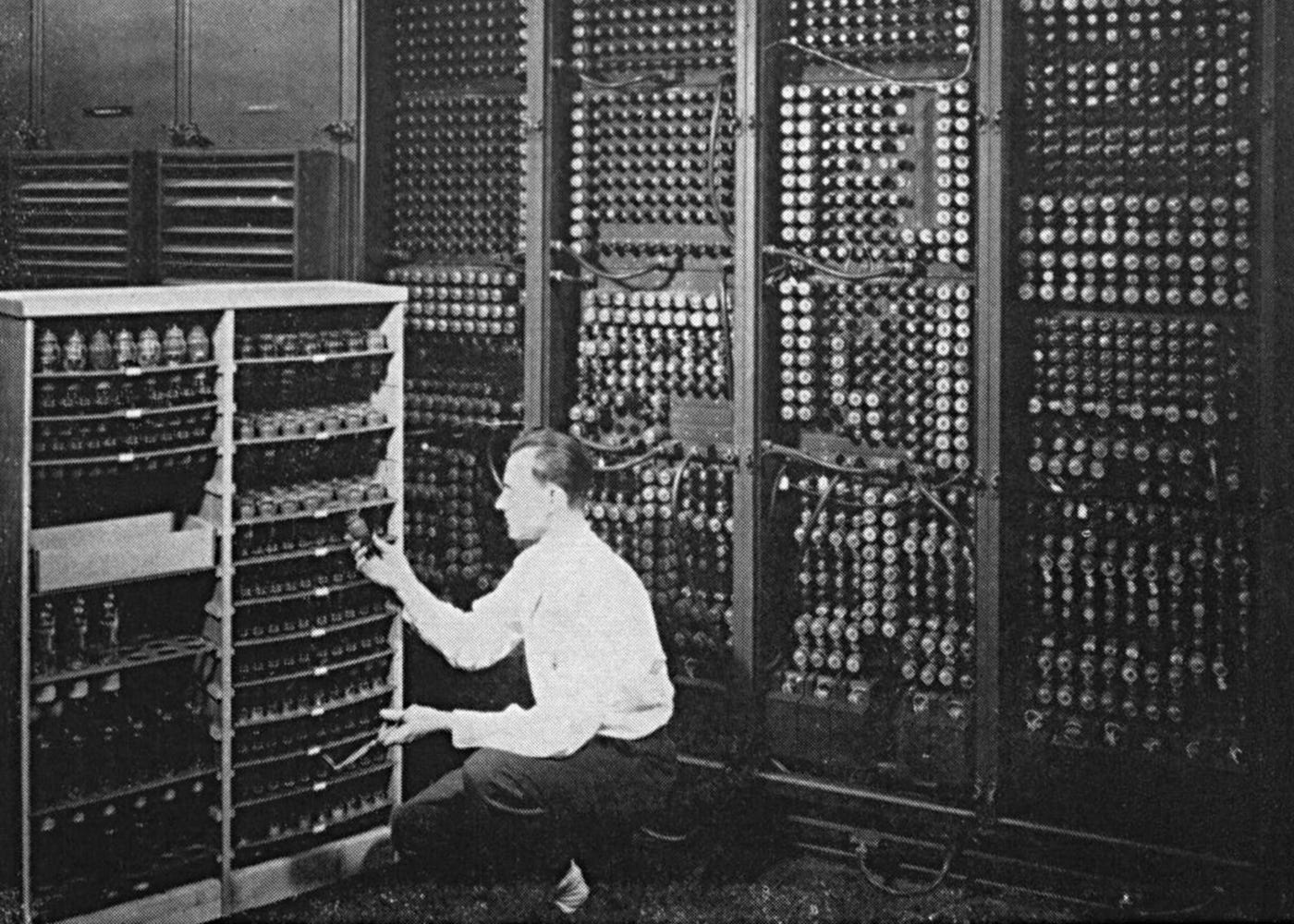

The first computers were for calculating. The computer was conceived as a device to help solve mathematical problems quicker than humans could do so alone, while also helping to eliminate human error. They were to be operated by engineers and specialists. The development of these computers was accelerated by that timeless engine of creativity, productivity and innovation: the desire of humans to kill one another as efficiently as possible, and in large numbers.

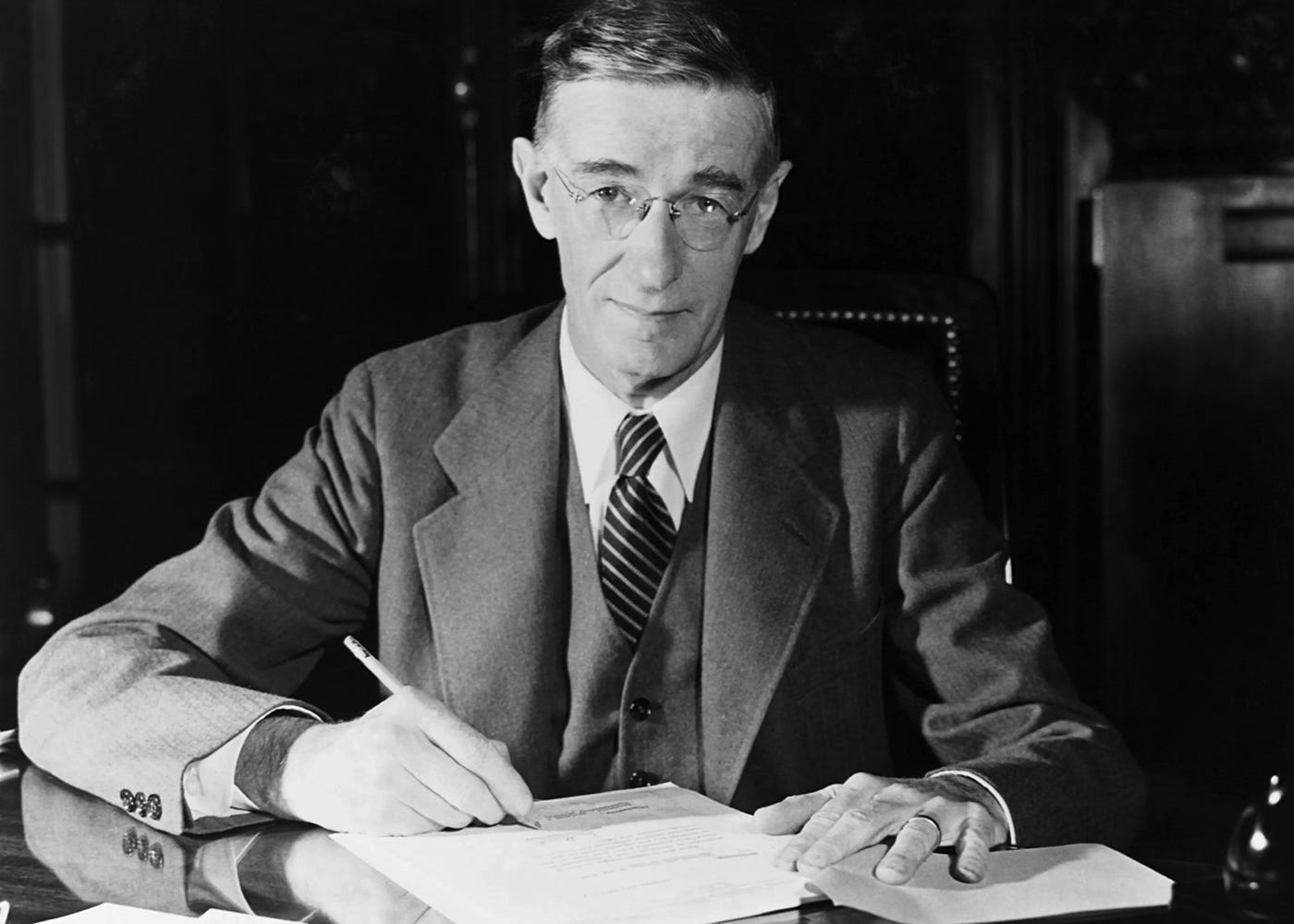

In 1940, as Nazi armour swarmed into France, the American engineer and inventor Vannevar Bush urgently sought an audience with President Roosevelt. Bush, a professor at MIT, had built the world’s first analog electrical-mechanical computer. His machine was an important landmark in the history of computing, and it had a particularly useful military application – generating artillery firing tables, which was the type of task that occupied early computers, essential battlefield calculations that could be made much faster than humans could accomplish by themselves.

During the First World War, Bush had felt that the development of US technology had been hampered by a lack of co-ordination between civilian scientists and the military. Alarmed by the speed of the Nazi advance in the opening stanzas of the Second, he appealed to Roosevelt to establish the National Defense Research Committee and, later, the Office of Scientific Research. These organisations, both chaired by Bush, would co-ordinate military and civilian scientific resources and research with the aim of achieving technological advantage in the war. They would also create what has been called America’s “military-industrial-academic” complex, a confederacy of the Pentagon, large corporations and academic research institutions that would turbo-charge the development of computer technology between the 1950s and ‘80s.

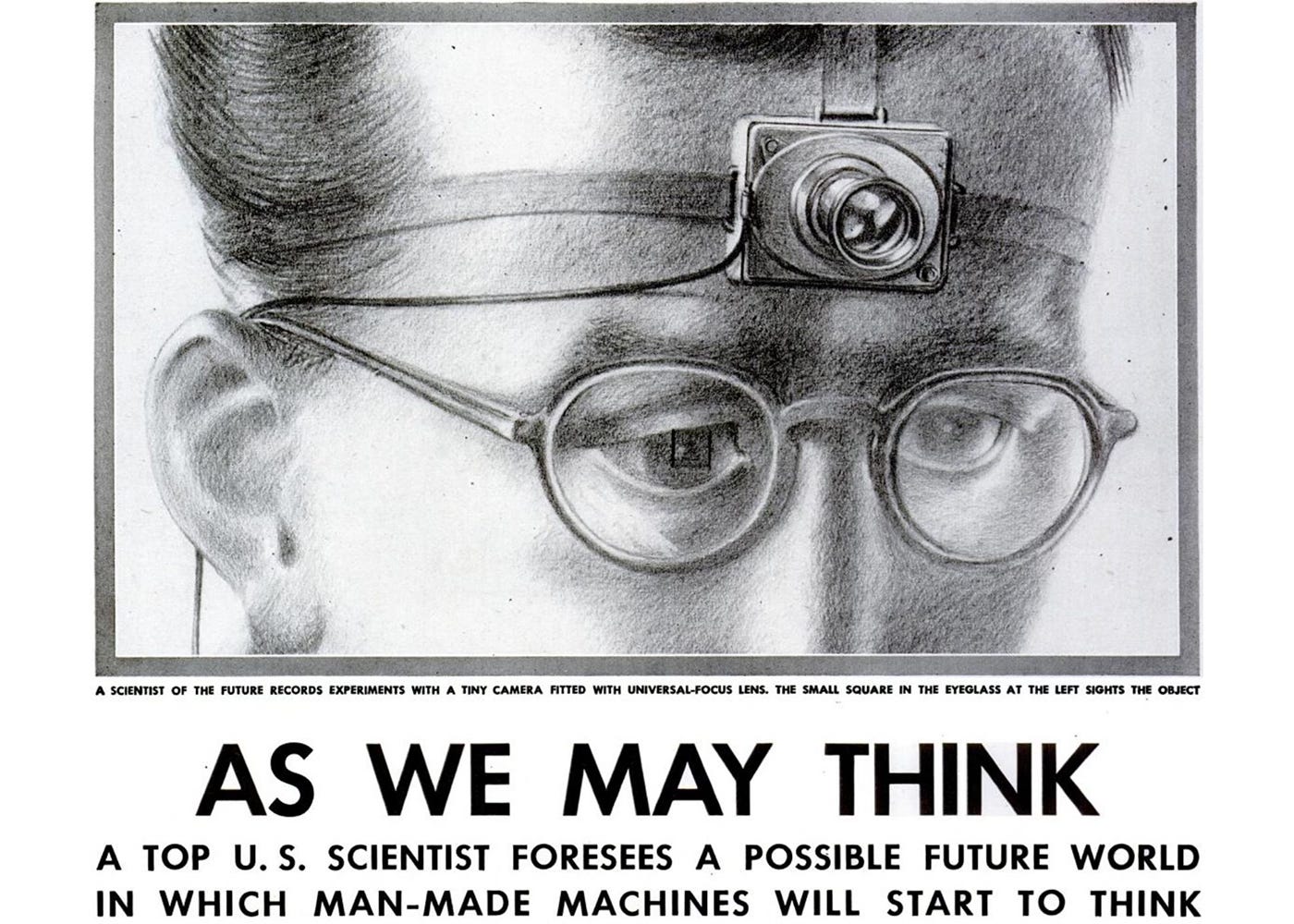

Bush was not only a pragmatic organiser, he was also a dreamer and futurist who stared out over the horizon of technology, and thought about where man and machine may take one another. In July 1945, one month before his Manhattan Project unleashed the rolling nuclear fire that engulfed Hiroshima, Bush published an article in The Atlantic entitled As We May Think. “The applications of science have built man a well-supplied house”, Bush wrote, “They have enabled him to throw masses of people against one another with cruel weapons. They may yet allow him truly to encompass the great record and to grow in the wisdom of race experience”. He went on to describe a personal device that he called a Memex:

Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanised file and library. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records and communications and is mechanised so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged, intimate supplement to his memory.

What Bush had described with his memex, was a conceptual progenitor of the networked personal computer, a device that could enhance the cognitive ability of the individual subject, a machine that complements the individual human life as it is lived. This was a profound imaginative leap from what computers were at the time, huge mainframes chugging away in labs and operated by dedicated technicians.

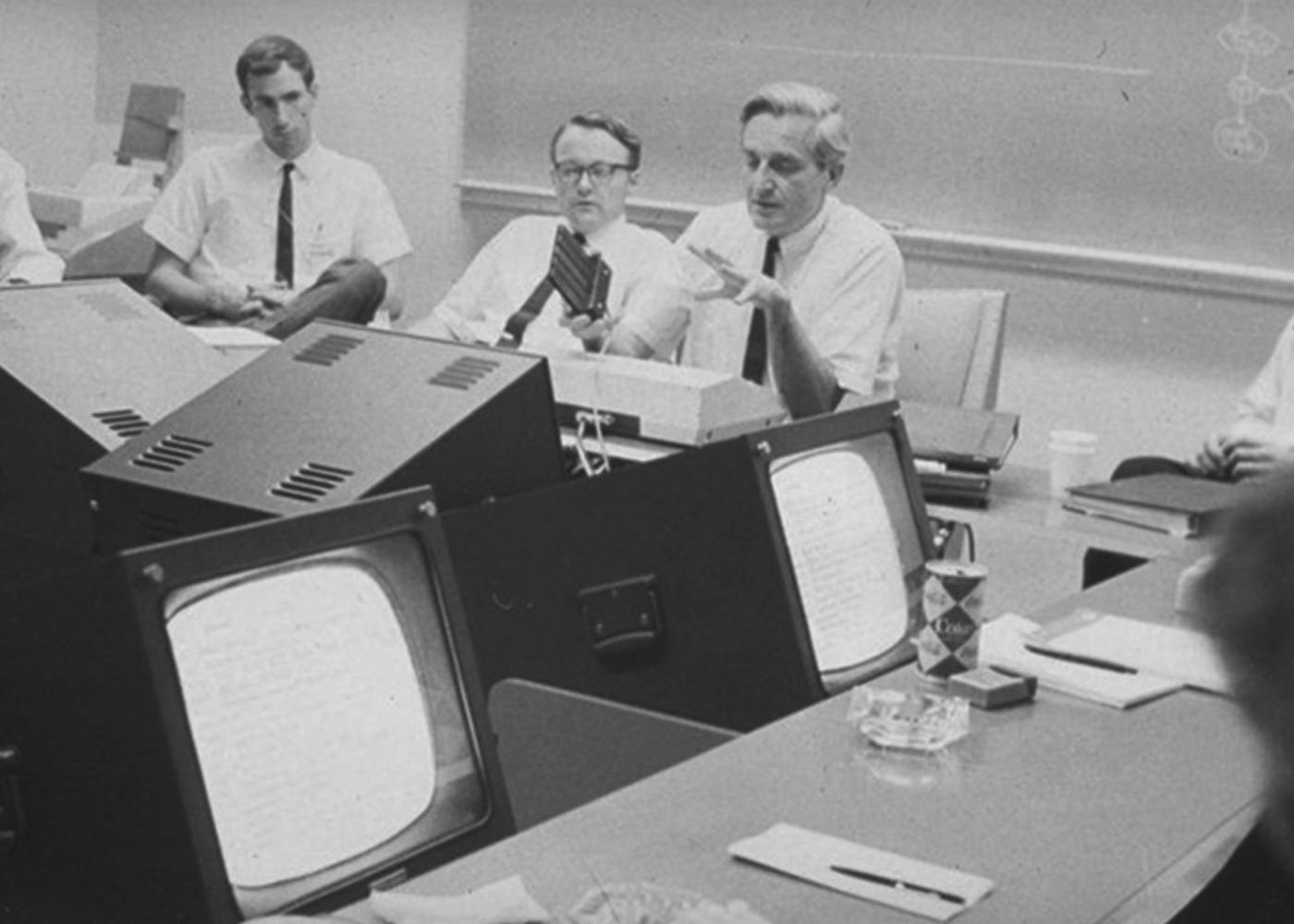

In 1951, six years after Bush had conceived the memex, another computer scientist at MIT, J.C.R Licklider, described a system that would further close the gap between man and machine: “time-sharing”. Time-sharing removed the mediating authority of the computer technician from the relationship between the computer and its user. Prior to time-sharing, users had to hand punch cards or tape to computer technicians, who would exit in the direction of the computer mainframe, returning hours or even days later to loftily announce the results. Time-sharing permitted multiple terminals to communicate directly with the mainframe simultaneously, users could get results almost instantly, in discrete communion with the computer.

In 1960, Licklider published a paper entitled Man-Computer Symbiosis, “The hope is”, he wrote, “that, in not too many years, human brains and computing machines will be coupled together very tightly, and that the resulting partnership will think as no human brain has ever thought and process data in a way not approached by the information-handling machines we know today”.

Two years later, Douglas Engelbart, an electrical engineer at The Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park, published Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework. Engelbart was in thrall to Bush’s vision of the memex, and had dedicated himself to realising it, “By ‘augmenting human intellect’”, he said, “we mean increasing the capability of a man to approach a complex problem situation, to gain comprehension to suit his particular needs, and to derive solutions to problems”.

Engelbart’s theories built on those outlined by Bush and Licklider, he described a close personal relationship between man and machine, one which is variously “symbiotic”, “individual”, and intended to “augment” the natural abilities of the individual.

Engelbart’s mission was ideological and solutionist, he wanted to make the world a better place. He thought that computer technology could harness the collective intelligence of mankind in order to overcome problems of such complexity that they would have previously been thought insoluble. But while he imagined that the genesis of this effort should be the ability of the human individual to “augment” and extend their abilities through a close personal relationship with their own computer, he thought that the end would be a supreme collective project joined by networked individuals collaborating to surmount the challenges facing mankind. Engelbart was given his head, and he founded his Augmentation Research Center (ARC) within the Stanford Research Institute, in part with funding from J.C.R Licklider.

The combined theories of Bush, Licklider, Engelbart and the eventual arrival of ARC led to something of a schism in the early history of computer technology. As John Markoff, in What The Dormouse Said, How the Sixties Counter-culture Shaped The Personal Computer Industry, puts it:

Engelbart’s view of the future of computing in the Sixties ran directly counter to the precepts of the mainstream of the computing business. The era was dominated by a belief that artificial intelligence was at hand and would soon create a world dominated by thinking machines. Engelbart’s notion of work groups where human intelligence was instead “augmented” by computers was thought of as quaint and besides the point. It might be suited for the office, or it could improve the skills of a secretary, but it certainly could not be considered computer “science”.

This theme recurs in the work of the other techno-futurists to have conceptualised personal computing; consider Licklider’s prediction in Man-Computer Symbiosis that “the resulting partnership will think as no human brain has ever thought”. They all stalked the idea that in the process of adapting computers to augment human capabilities, it is conceivable that the human mind will in turn undergo a process of adapting to the logic and demands of its machines. This is, of course, precisely what we have seen in our contemporary history, often with distressing consequences, as Engelbart’s vision of what computers should be ultimately became the pre-eminent one. John Markoff in What The Dormouse Said:

Engelbart…had been the first to demonstrate a vision that led directly to today’s computing world. He came early on to understand that computers had the ability to range far beyond crunching numbers. He foresaw that computers would become machines that could help human beings communicate and extend the reach of their intelligence…from that original inspiration, both personal computing and the internet ultimately emerged.

This is why attendees at Engelbart’s Mother of All Demos described it as “Moses opening the Red Sea”, what Engelbart was describing was not a new computer, but a new way of being, and while he experimented with computer technologies, other organised scientific experiments were taking place in Menlo Park, in particular those involving psychedelic drugs, in which Ken Kesey was a participant. As we saw in the first part of this series, the two tribes, Engelbart’s techno-futurists, and Kesey’s religious hippies, eventually found each other and embarked on their shared mission to change the world. Markoff:

Engelbart’s “Augmentation Framework” was brought to life by a small band of researchers who were deeply influenced by the political and cultural climate of the mid-peninsula…a tiny band distinguished by their long hair and beards, rooms carpeted with Oriental rugs, women without bras, jugs of wine and on occasion the wafting of marijuana smoke.

The Techno-Hippies

The long-haired stoners that Markoff describes padding through the corridors of ARC were young members of the Bay Area counterculture, many of them had remained at the universities and research labs expressly in order to evade being drafted into the Vietnam war.

As we have seen, Engelbart’s vision was a fundamentally utopian one. He imagined that the computer of the future would not be a tool to help execute discrete mathematical processes, as had been the case in the past, but would be a personal device with the potential to become integral to almost every aspect of human activity, an extension of the self. In Augmenting Human Intellect he described a small, handheld computer:

an artifact that was essentially a high speed, semi-automatic table-lookup device—cheap enough for almost everyone to afford and small and light enough to be carried on the person, [that] could hold the equivalent of an unabridged dictionary, and that a one-paragraph definition could always be located and displayed on the face of the device by the average practiced individual in less than three seconds…how would our vocabulary develop, how would our habits of exploring the intellectual domains of others shift, how might the sophistication of practical organization mature, how would our education system change to take advantage of this new external symbol-manipulation capability of students and teachers (and administrators)?

A utopian belief in the promise of some agent or technology to radically alter human societies also animated the hippie movement. Initially, this had been LSD, then various combinations of new-age spiritualism, Eastern mysticism and novel psychotherapies, now, the potential of computer technology became the focus of their utopian fantasies. When Stewart Brand invited Ken Kesey on a tour of ARC, the astonished Kesey anointed Engelbart’s oNLine system, “the next thing after acid”.

The hippies fundamentally rejected the radical prospectus of the New Left and the political side of the counterculture. In general, they believed that social change would arrive as a consequence of personal liberation, of individuals who had transformed themselves and their way of thinking, and that politics were irrelevant, a distraction.

As we saw in the previous part, the hippie’s worldview chimed with the libertarian philosophies of Ayn Rand. In describing the type of person who might benefit from the augmented future, Engelbart wrote, “let us consider an augmented architect at work”. Although most probably entirely co-incidental, it is in interesting that Engelbart’s illustration reached for the figure of an architect; it was an architect whom Rand cast as the protagonist in The Fountainhead, her foundational defence of individualism. The architect is an appealing hero within individualist, libertarian fantasies because they are simultaneously a designer, aestheticist, problem-solver and a mathematician, a single, individual creative mind, who accomplishes a grand technical-artistic vision alone. The architect and, we might imagine, the computer programmer, emerges from the libertarian cosmology as the ideal Nietzschean archetype, the free individual who will remake the world.

I explored the ideology of the Hippies in depth in Lessons from the Counterculture, and noted that many of the ‘60s radicals ended-up as Republican-supporting conservatives, venture capitalists and wealthy businessmen, which, I feel, is entirely congruent with their ideology:

Perhaps the Pranksters, the Hippies, and finally the Yippies, had a natural ideological affinity with the Liberal Capitalist state, and had been prepared to strike a bargain all along… Although these departures to the Right might appear to be resignation borne of defeat, or else a time-honoured feature of the exodus from youth to middle-age, I think they are consistent with the ideology of the Counterculture, latent within it from the beginning. The Libertarianism and narcissism that were at work in Ken Kesey’s Pranksters, and expressed themselves within the Hippie movement, the defence of inclination as authenticity in One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest and its politics of “being true to oneself”, the same politics that led to fellowship with the Hell’s Angels, all of this is congruent with the free-market Libertarianism of the Neoliberal Right.

The Counterculture of the 1960s provides us with a guide as to where…ideological confusion can lead. The misdirected expressions of individuality, the…inability to articulate the ideal relationship between the individual and society, the Hippies’ emphasis on a politics of individual libidinal desire, which is, ultimately, the basis of capitalist ideology, the communal-individualism in which the communal space is fractured into identity groups and re-imagined as an extension of individual identity, all of this contributed, in my view, to the emergence on the Right of a radical form of the politics of individualism and privatisation in the form of Neoliberalism. And it’s perfectly logical that so many of the Countercultural Left became venture capitalists.

The hippies were also given to conspiracism and paranoia. Part of this was that paranoia, and the perception that there is some unseen matrix of patterns and connections governing the world, is a consequence of psychoactive drug use. Hippies loved meandering, stoned discourses on the hidden universal truths that could be revealed by psychedelic drugs, but which otherwise remain obscure, concealed from us by the evil machinations of The Man and his quest to impose social control.

Another part of it was the hippies’ blunt and unsophisticated concept of The Man as signifier of the dynamics of power: all systems of power were inherently, even self-consciously, authoritarian, immoral and corrupt. This notion stood in contrast to the Leftist understanding that systems of power arise as a natural consequence of human social organisation, and that what is important are the goals to which that power is directed, its distribution and mechanisms of accountability; in other words, politics. The Left’s mission was to try to acquire control over the institutions of political power, whereas the hippies felt that this was naïve and self-defeating, and that the goal had to be liberty from the demands and supervision of those institutions. For the techno-hippies, computers represented an opportunity to achieve that goal.

“The Counter-Culture’s scorn for centralized authority provided the philosophical foundations of the entire personal computer revolution”, Stewart Brand would later say, “the freaks who design computer science will wrest power away from the rich and powerful institutions. Computers are coming to the people. This is good news, the best since psychedelics.”

In his series All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace, the documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis describes the techno-hippies as trying “to create a stable world” through computer technology:

An idea was emerging that said that the new computer technologies could turn everyone into heroic individuals. A vision of a society in which the forms of political control would be unnecessary because computer networks could create order in society, without the need for political control…The networks would create self-regulating feedback loops and the world would be stable, with every individual free to pursue their own heroic desires…They thought they could build a society without hierarchy in which, because people are linked by the machines, stability and order would emerge.

Where I depart marginally from Curtis is in the emphasis that he places on the hippies’ desire for “a stable world” and non-hierarchical communities. While it’s true that they were generally hostile towards hierarchies, and thought that computers would change the way in which societies were structured, I think that the hippies were motivated less by a search for a new system of social order, and more by a simple narcissistic desire to do whatever they wanted, without being subjected to interventions from the dominant power (or any power, in fact).

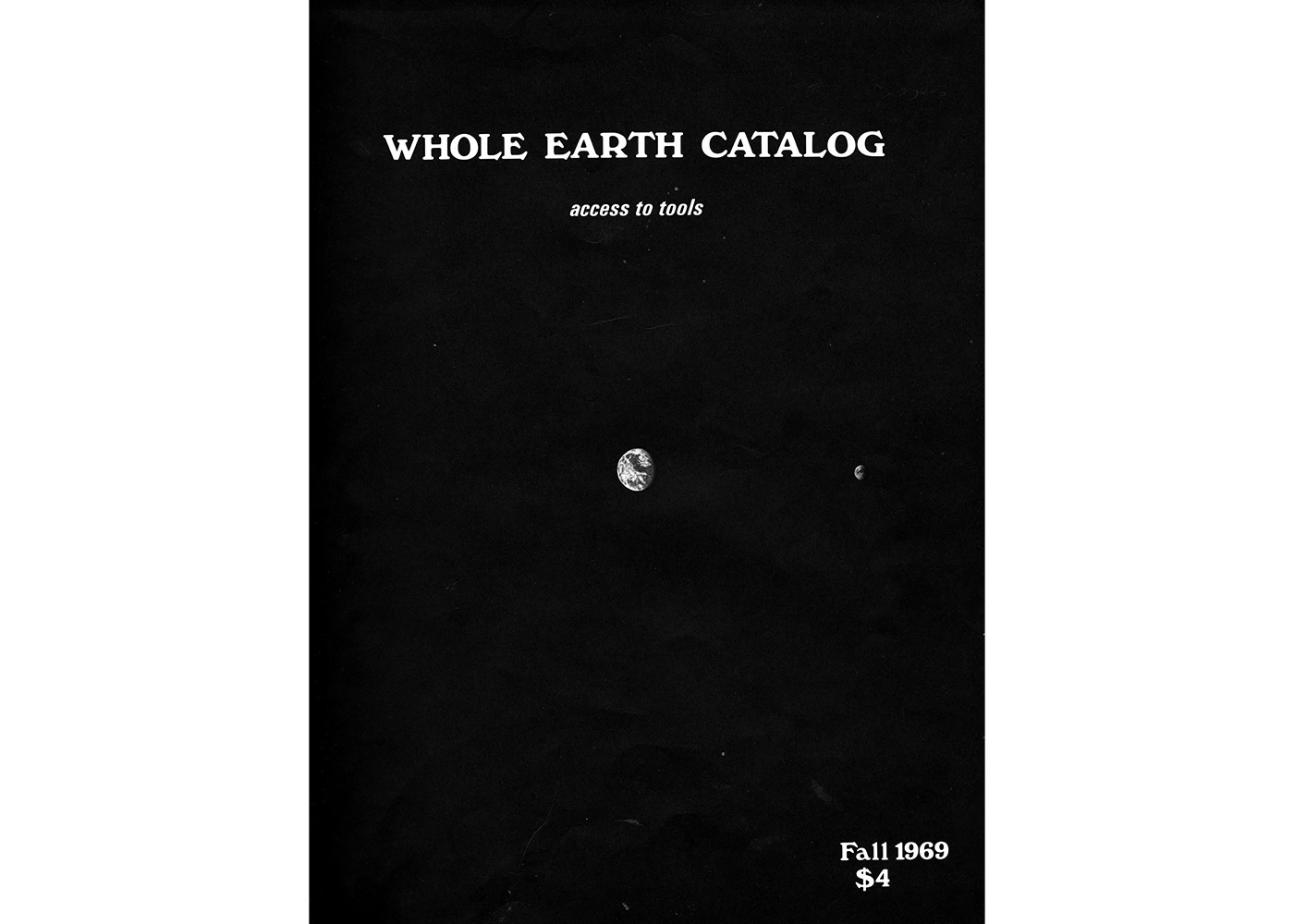

After Douglas Engelbart’s Mother of All Demos in 1968, the techno-hippies started to form into a tribe, and coalesce around a set of ideas. A month after participating in Engelbart’s demo, Stewart Brand published the inaugural edition of the Whole Earth Catalog, a journal-cum-marketplace for the techno-hippie community. John Markoff, What The Dormouse Said:

“It helped a scattered community that was in the process of defining itself find an identity. The Catalog…had originally been intended as a resource for a way of life less dependent on the power and influence of modern industrial society… the second half of the short introduction neatly captured that various threads that would soon come together to liberate the computer from large, impersonal institutions: ‘a realm of intimate, personal power is developing – power of the individual to conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, shape his own environment, and share his adventure with whoever is interested. Tools that aid this process are sought and promoted by the WHOLE EARTH CATALOG’

Brand later expanded on some of the foundational beliefs in this “realm of intimate, personal power”, in his 1995 article for Time Magazine, We Owe It All To The Hippies, Brand wrote:

As Steven Levy chronicled in his 1984 book, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, there were three generations of youthful computer programmers who deliberately led the rest of civilization away from centralized mainframe computers and their predominant sponsor, IBM. "The Hacker Ethic," articulated by Levy, offered a distinctly countercultural set of tenets. Among them:

"Access to computers should be unlimited and total."

"All information should be free."

"Mistrust authority - promote decentralization."

"You can create art and beauty on a computer."

"Computers can change your life for the better."

Brand identified with Ken Kesey’s apolitical, religious side of the counterculture, what he called the “psychedelic side”, and disdained the New Left – “power to the people was a romantic lie”, he would later say. But a political outlook can be discerned from a survey of his life and work, one which can best be described as Libertarian-Capitalist. He was expressly anti-communist, held attitudes that have been described as “conservative”, and took an interest in business, finance and the power of capital. It was a political disposition that became generally pervasive among the techno-hippies. We Owe It All To The Hippies:

As they followed the mantra "Turn on, tune in and drop out," college students of the '60s also dropped academia's traditional disdain for business. "Do your own thing" easily translated into "Start your own business." Reviled by the broader social establishment, hippies found ready acceptance in the world of small business. They brought an honesty and a dedication to service that was attractive to vendors and customers alike. Success in business made them disinclined to "grow out of" their countercultural values, and it made a number of them wealthy and powerful at a young age.

One such figure was Stewart Brand himself. The Whole Earth Catalog had proved to be a spectacular success, but after two years (and accompanying burn-out) Brand took the decision to end its print run. He threw a party to mark the occasion, at which he appeared with $20,000 in cash – equivalent to $150,000 today. 20k was the sum that Brand had used to start the Catalog, and so at the moment of its demise, he felt inspired to re-invest the capital.

By 1972 the contours of the technological future were defined, and so was the governing ideology: computers would be personal, designed to augment the abilities and enhance the aspirations of the private individual, but networked for group communication and collaboration. Under the guidance of the techno-hippies, the personal computer revolution would be anti-establishment, libertarian, entrepreneurial, with a seam of conspiracist paranoia running through it (notwithstanding the contradiction that much of the support would come from central government).

It would be a Libertarian-Capitalist empire based in and around the universities, research labs and hippie communes on the San Francisco Peninsula and possessed of the belief that in technology would be the final liberation of mankind.

All of which brings us to the role of money, and Stewart Brand’s twenty-thousand dollars…

Next: Techno-Fascism Part #3: The Money