Techno-Fascism Part#3: The Money

“Information wants to be free. And it wants to be very expensive”.

“Information wants to be free. And it wants to be very expensive”.

- Stewart Brand

The previous part in this series explored the ideologies at work in the personal computer revolution, and ideas of the techno-hippies who fomented that revolution. It was an individualistic, solipsistic, anti-establishment, anti-hierarchical, entrepreneurial form of Libertarian-Capitalism. It had an ambivalent relationship to power - hostile to political authority and the state, yet financed by the state and in particular the Pentagon; a tension which the hippies were conscious of. It fell within the lineage of Ken Kesey’s “religious”, or “psychedelic” counterculturalism, from which it inherited a self-centred, self-serving dimension. And it produced private, commercial enterprises that were clearly going to be worth a lot of money, something that, back in the ‘60s and ‘70s, some of the nominally anti-Capitalist hippies found uncomfortable, among them a young anti-war activist named Fred Moore.

Moore had become interested in computers as potentially useful tools for political organising. He had served jail time for refusing to join the Vietnam draft, and after his release in 1967 lived on the breadline around the San Francisco Peninsula, where he engaged in community activism and cultivated a disdain for money, which he felt disfigured all human relations.

In 1971 Moore attended a party thrown by Stewart Brand, to mark the final print run of the Whole Earth Catalog, at the Exploratorium Science Museum in San Francisco. As the gathering of one thousand raucous Catalog fans danced, played volleyball and huffed nitrous oxide while the clock rolled past midnight, Brand took to the stage and announced that he had with him $20,000 in $100 hundred dollar bills, to be spent however the collected hippies saw fit.

Brand’s idealistic notion that the wisdom of the crowd would produce sensational, inspired ideas on how to deploy capital to the benefit of mankind proved to be idiotic. Hours of tortured debate ensued, with drunk hippies firing off unpromising suggestions and $5,000 of Brand’s $20,000 mysteriously disappearing as it passed between the various proposers.

Fred Moore was moved to fury. Where Brand saw an opportunity for dynamic, non-hierarchical investment decisions (an opportunity that he was rapidly losing faith in), Moore perceived cacophonous rancour, the division and avarice that always attended the appearance of money. He made several interventions throughout the night, inveighing against the psychotic despotism of money and appealing to the crowd to reject it in favour of using the gathering as an opportunity to forge relationships and freely collaborate. As dawn broke and the sun climbed above the sparkling waters of San Francisco Bay, the partygoers voted to take the remaining $15,000 from the prone fingers of an exhausted, vanquished Brand and give it all to Fred Moore, the one guy who didn’t want it.

The arrival of Venture Capital

When Silicon Valley established itself in Palo Alto in the early 1950s, the new, innovative technology companies that sprang up also, initially by happenstance, attracted novel forms of finance.

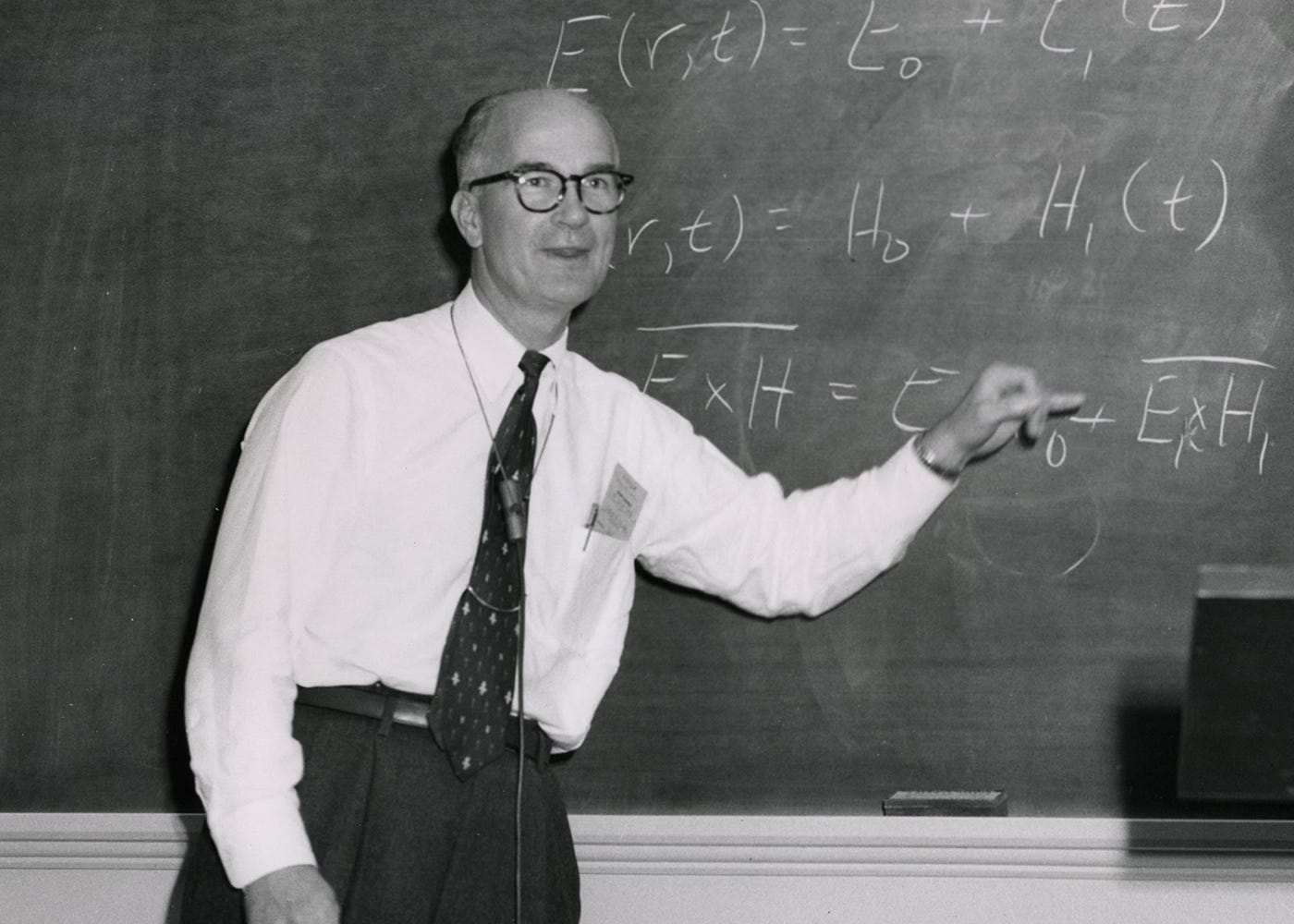

One of Palo Alto’s first tenants was Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory, a semiconductor research lab founded by the Nobel prize-winning physicist William Shockley. Although clearly a gifted physicist, Shockley was a profoundly unpleasant specimen, and difficult to work for. His reputation was that of an imperious bully, who routinely intimidated and humiliated his employees. He was also a racist, who dedicated his autumn years to eugenics, and the pursuit of proof that black people were an inferior species.

In 1957, eight of Shockley’s most gifted researchers concluded that they had seen enough, and resigned en-masse from Shockley Semiconductor, earning themselves the sobriquet “the traitorous eight” in the process. The eight intended to enter into direct competition with Shockley, but lacked the money to do so. Personal connections eventually brought their proposal to a young Wall Street broker named Arthur Rock, who was prepared to gamble that a group of people with such obvious ability were bound to achieve something extraordinary sooner or later.

The traditional method of privately financing a new venture was either to find a single corporate sponsor, who might be prepared to incorporate a new division, or to apply to funds operated by rich families, who would invest in interesting ideas that the banks refused to back. For the traitorous eight, Arthur Rock approached Sherman Fairchild, a wealthy playboy, founder of Fairchild Aircraft, Fairchild Camera and a suite of other enterprises. When Fairchild agreed to bankroll Fairchild Semiconductor for the eight, Rock’s company also cut themselves in on the action. It was the opening deal in a model of finance that would become known as “venture capital”.

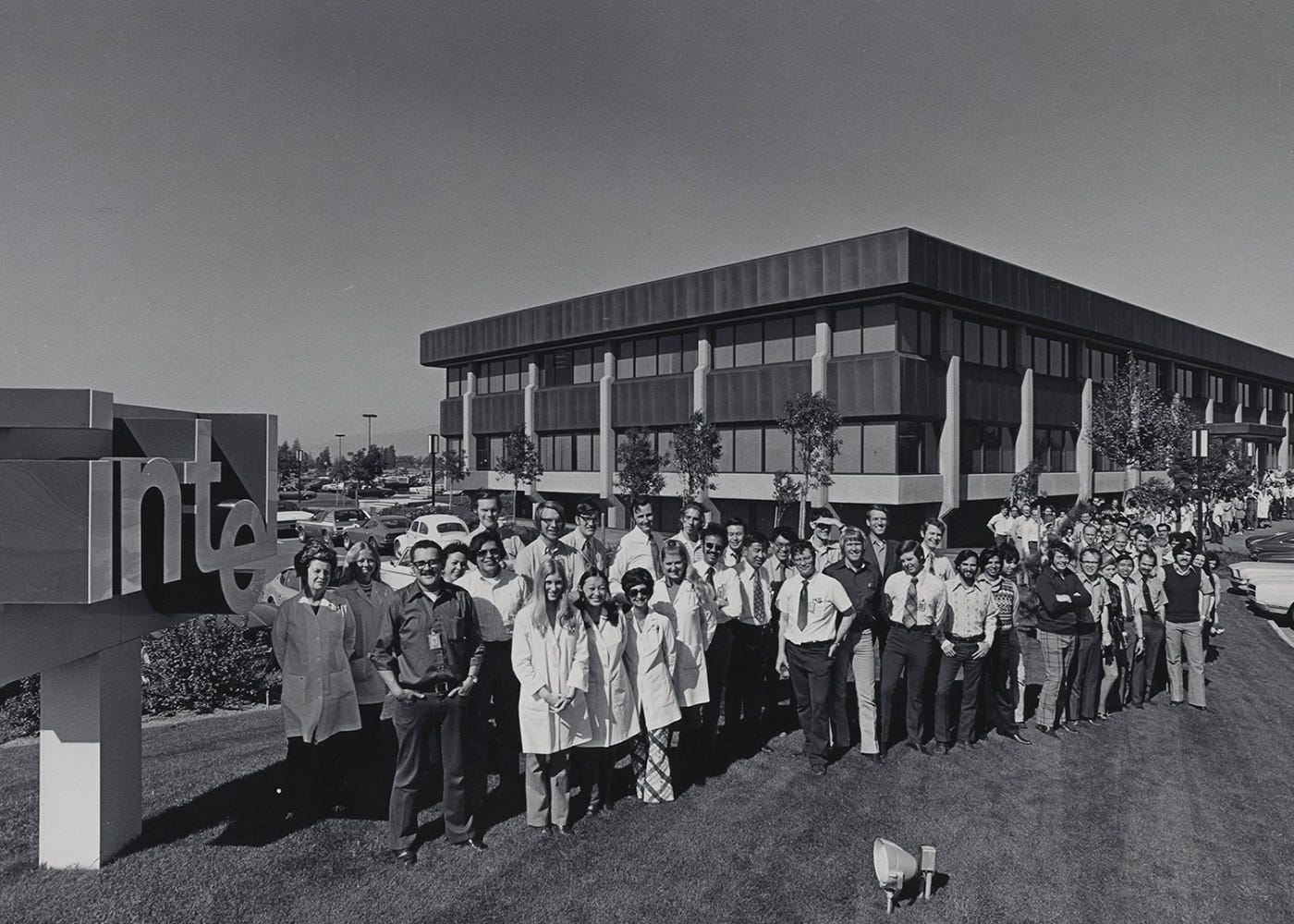

Fairchild Semiconductor and its founders went on to blockbuster success and the company became a progenitor of various “Fairchildren” – a succession of some of the most significant enterprises in Silicon Valley, including Intel. Arthur Rock arranged venture capital for many of these enterprises: start-up finance exchanged for a share of equity.

The money often went to charismatic entrepreneurs, and not necessarily a business plan, “I think talking to the individual is more important than finding out what they want to do” Rock would later say. As the economic model of Silicon Valley evolved, it became very focused on individual entrepreneurs, “founders”, as they eventually became known, and departed from the economic logic of traditional businesses which are, as a first principle, expected to post profits.

The cyber-utopian thinker John Perry Barlow (of whom we will hear much more in this series) would later say, “the best way to raise demand for your product is to give it away”, and this maxim neatly encapsulates the rationale of Silicon Valley’s venture capital-driven model as it would evolve over the decades. With its focus on charismatic individuals and savants, the model has proven itself able to withstand enormous financial losses, so long as a given enterprise is achieving visibility, market share and an escalating stock price. It has wrought untold damage on our economies and societies, a subject which we will revisit later in this series.

Fred Moore’s Homebrew

Back in 1971, Fred Moore was engaged in what we might consider to be a micro, street-level version of venture capital investment.

He tremulously dug up the Whole Earth Catalog money from his back garden and invested it in various community enterprises around the San Francisco Peninsula. Success was variable and Moore had to reluctantly assume debt-collection duties which, naturally, he detested; his stress was further amplified by a second infusion of $15,000 from Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth project.

As a mathematician, Moore had an instinctive interest in computers, but was suspicious of the entire sector, which he saw as an organ of The Man – giant mainframes controlled by unsentimental and repressive corporations. He was, however, intrigued by the concept of smaller, personal computers, which could be deployed to create networks and facilitate the free exchange of information, beneath the notice of giant technology companies and their imperial designs.

Moore started to pay out the Whole Earth money in loans and grants to organisations who would provide computer access and education on the peninsula, he became part of a small, local community of micro-computer enthusiasts and hobbyists, at the centre of which was The People’s Computer Company – a newsletter with a declared mission to restore computers, which it claimed had been used against the people, to the control and service of the people.

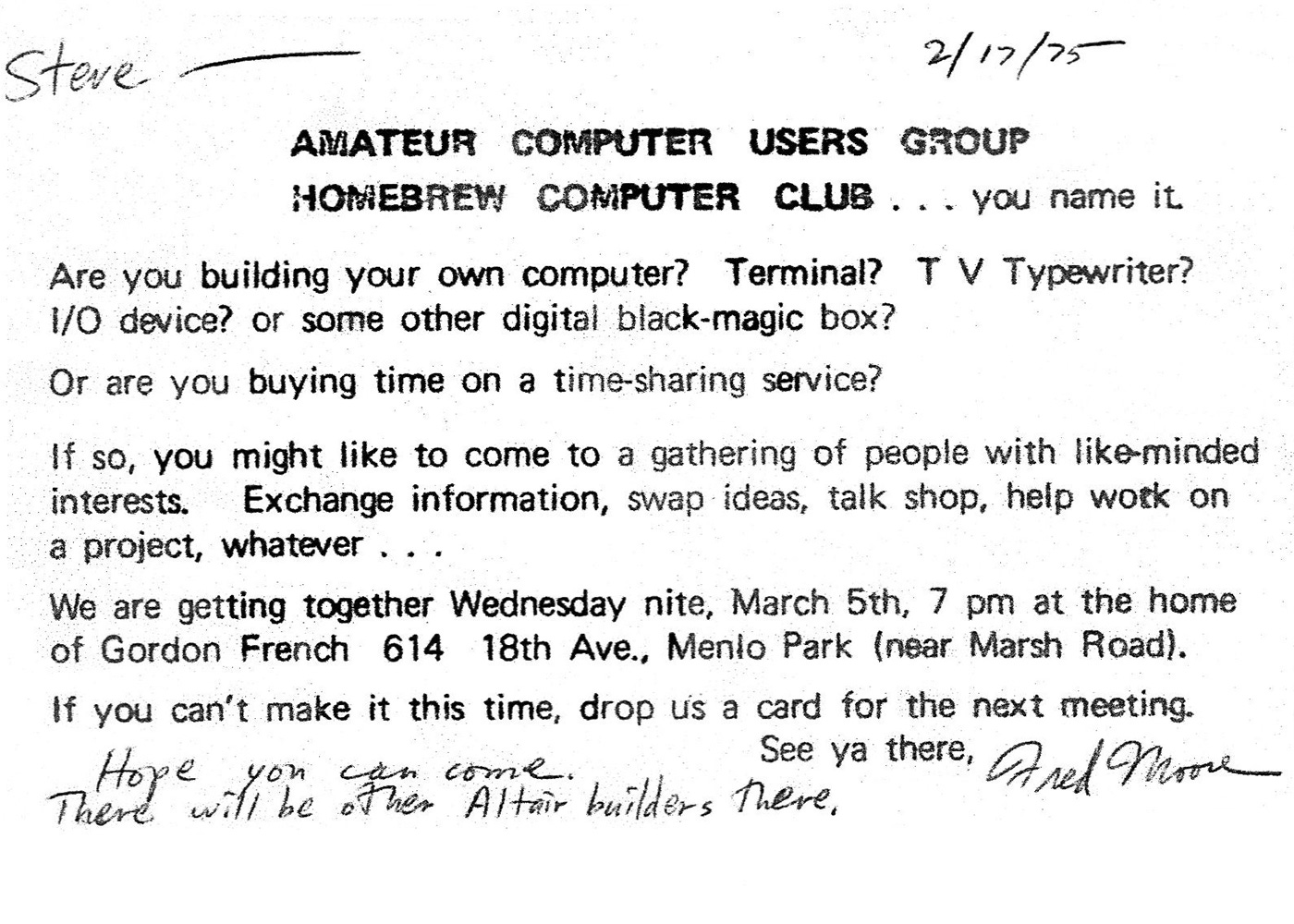

In the spring of 1975, Fred Moore, along with other veterans of The People’s Computer Company, founded the Homebrew Computer Club, an open community in which amateur computer technicians and hackers could share, network and collaborate. It was the kind of forum that Moore had advocated for at Stewart Brand’s party in the Science Museum four years earlier, and it marked the moment at which computer development broke out of the technology companies and research labs, and started to circulate freely among enthusiasts in the general population.

The ethos of the club energetically endorsed the first part of Stewart Brand’s aphorism, “information wants to be free. And it wants to be very expensive” (in time many club members would become equally positive about the second clause). But for the Homebrewers “free” meant not only “freely accessible”, it also meant “free of charge”.

The Homebrewers embraced the ethic of piracy that would become prevalent during the early years of the web - an ethic of which Napster would be a representative example. Two of the club’s most celebrated alumni, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, had started out building “blue boxes”, devices that hacked the Bell telephone network and enabled the user to make free long-distance calls. There was a general culture of disregard for property rights, and a feeling that discovery of the luminous technological future depended the free circulation of information.

The club’s philosophy went on to inspire the Free Source and Open-Source movements, which I won’t go into in this series, except to say that the Homebrewers modelled a form of technology development that emphasised community and collaboration in opposition to proprietorship and commercial protectionism. They were less explicitly concerned with the countercultural individualism of Kesey Hippies like Stewart Brand.

Where we might see the Homebrewers’ spiritual antecedents in the counterculture of the ‘60s, is in The Diggers, whom I covered extensively in Lessons from the Counterculture Part 5:

The Diggers [were] an anarchist collective that perhaps best embodied the Haight’s hybrid politics of communal-individualism, in which the interests of community are promoted through Libertarian individualism, anti-materialism and anti-statism…In an early manifesto they proclaimed “the US standard of living is a bourgeois baby blanket for executives who scream in their sleep…our fight is with those who would kill us through dumb work, insane wars, dull money morality… Any important human occupation can be done free… Give up jobs. Be with people. Defend against property”… The Diggers organised “Free Stores”, ramshackle charity shops in which all the donated goods were free. They ran a soup kitchen in Golden Gate Park, where mal-nourished hippies queued to step through the “free frame of reference” and receive a bowl of meat and vegetables. They organised healthcare clinics staffed by medical students and crash pads where the homeless could find shelter.

The Diggers shared Fred Moore’s abhorrence of money, and the constraints that it placed on human existence. They sought to replace “dull money morality” with their ethic of “free”, the same basic concept that an inflamed Moore had struggled to advocate at Stewart Brand’s party, and the same ethos that animated the free-experimentation of the Homebrew computer hobbyists. But, back in the ‘60s, The Diggers (and the other groups that experimented with alternative ways of living in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighbourhood), had had an uncomfortable collision with reality, something that I described as the “Starbucks Paradox”:

The Haight encountered what we might call the “Starbucks Paradox”, a facetious objection beloved of the Right (and sometimes idiotically endorsed by sections of the Left) which had its glory years during the anti-globalisation demos of the early millennium and into the post-crash “Occupy” era. The Starbucks Paradox holds that it is impossible to advance a critique of Capitalism if you have recently purchased a coffee from Starbucks, or bought something from Amazon, or, latterly, owned an iPhone/Macbook. This was the objection levelled at [Bill] Graham – that in running a successful business, he was guilty of advancing Capitalism, and exploiting the community in the Haight.

What the Starbucks Paradox ignores, or pretends to ignore, is that when both the global economy and the nation state are arranged according to the rules of Capitalism, then it is not possible to exist outside of Capitalism. That does not make Capitalism the immutable law of the universe and its metaphysics, as the Right likes to suggest, nor preclude it from critique. In fact, all that this facile argument achieves is to buttress the fallacious moral apology for Capitalism, which is to suggest that the Capitalist system is subject to ultimate democratic accountability via the mechanism of individuals exercising choice within the marketplace. This is why the Right loves the Starbucks Paradox, it’s an attempt to bait anyone credulous enough on the Left into accepting the premise of Capitalism, and it’s why anyone on the Left seriously advocating consumer behaviour as a means to fatally undermine Capitalism needs to give themselves a slap.

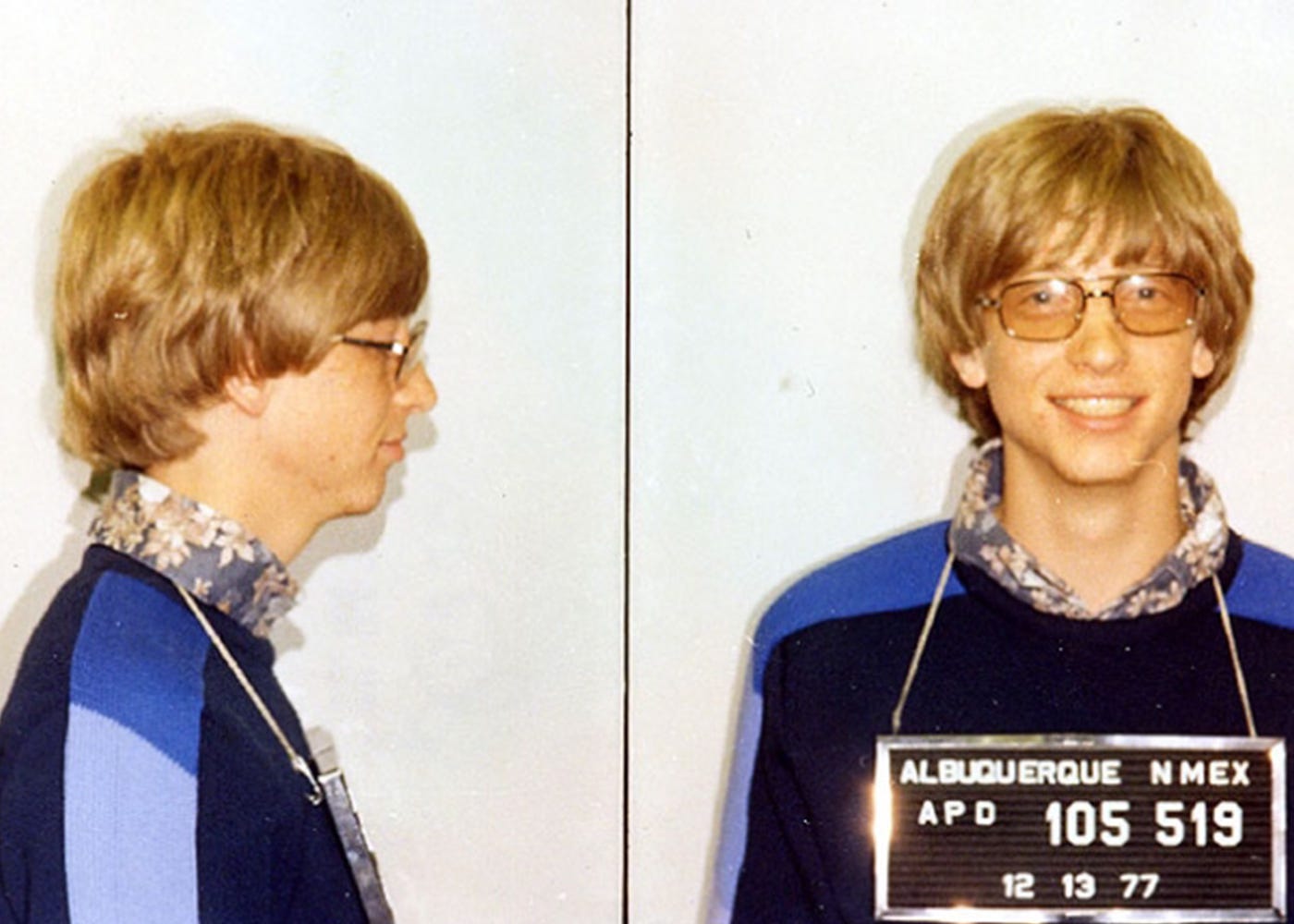

In 1976 the Homebrewers had a heated collision with the same reality that had confronted the exponents of the Starbucks Paradox a decade earlier. This time the voice of economic realism belonged to Bill Gates, a twenty-one-year-old computer programmer who was incensed that members of the Homebrew Computer Club had extensively distributed pirated copies of his new, groundbreaking software.

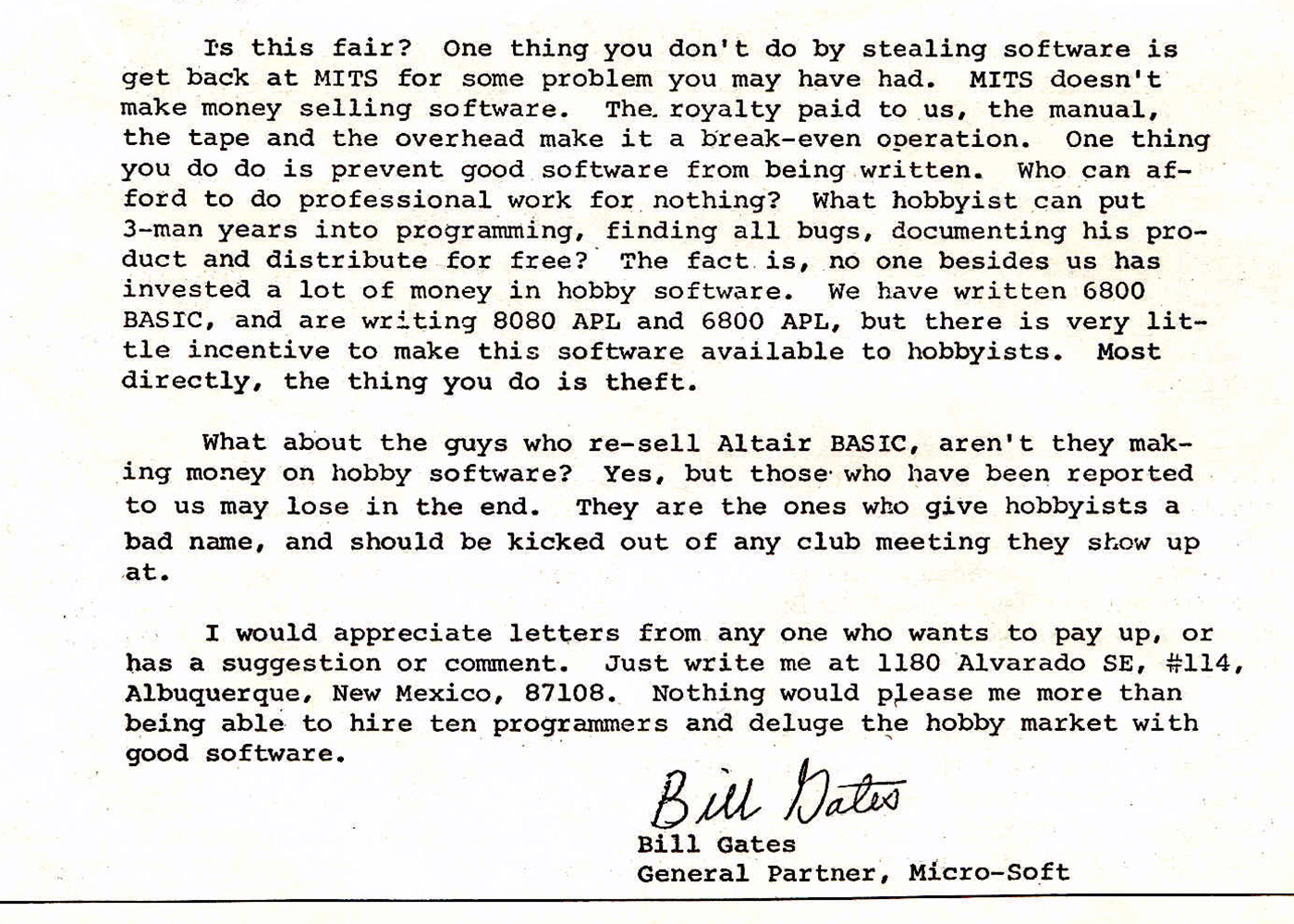

Gates attempted to appeal to the pirates on the basis of the prevailing system of business ethics, that is to say Max Weber’s notion of the “capitalist spirit” and Protestant work ethic. He published An Open Letter to Hobbyists in Computer Notes, The Homebrew Club Newsletter, People’s Computer Company and the Micro-8 Computer User Group Newsletter in which he wrote:

As the majority of hobbyists must be aware, most of you steal your software. Hardware must be paid for, but software is something to share. Who cares if the people who worked on it get paid? Is this fair?... The royalty paid to us, the manual, the tape and the overhead make it a break-even operation. One thing you do do is prevent good software from being written. Who can afford to do professional work for nothing? What hobbyist can put 3-man years into programming, finding all bugs, documenting his product and distribute for free?

Gates’s missive was taken by some techno-hippies as the classic profiteer’s complaint: an attempt to repress noble, collaborative, community-based endeavours to advance technologies for the betterment of mankind, in order that some individual can pursue his own personal fortune by wielding property rights.

The reality, of course, is far more complex, especially if viewed in context of the Starbucks Paradox. On what is the Homebrewers’ ethic of piracy and belief that Software should be free premised? If it is, say, the kind of vaguely anarcho-syndicalist beliefs espoused by Fred Moore and the Diggers, then Gates is correct and we run into the obstacle that, in a Capitalist economy, it is not possible to exist outside of Capitalism. While it is of course possible to develop free software or Open-Source software, this relies on the consent of the developer, and there will always be people, like Gates, who favour a proprietary model and do not give consent for the free distribution of their code.

If the idea is that software should be freely distributed in order to then enable some third order of proprietary Capitalism e.g to enable hardware development, which would then be subject to property rights and sold at a profit, then Gates is still correct, because he is right to draw attention to the arbitrary nature of these designations – on what basis is it held that hardware must be paid for but that software should be free?

If, finally, it is some form of vaguely libertarian viewpoint, in which one should be free to use whatever is available, without too much concern for rules, regulations and property rights, and that the mechanisms of the market and good intentions will impose equilibrium in the final analysis, then all of Gates’s arguments are irrelevant, and the laws of the jungle will decide the matter. I fear that it is this latter principle that was at work in Silicon Valley, particularly amongst the entrepreneurial hobbyists.

The more thoughtful techno-hippies were alive to the contradictions that spewed from the boiling furnace of computer innovation: Stewart Brand’s “Information wants to be free. And it wants to be very expensive”; the Cyber-Utopian John Perry Barlow’s “the best way to raise demand for your product is to give it away”. Brand, and others of this self-consciously libertarian bent, make a distinction in their concept of “free” between “libre” (no restrictions) and “gratis” (no cost), and it is the “libre” that emerged as the animating ethic of the computer revolution.

In his Open Letter to Hobbyists, Bill Gates argued for a grey, traditional Capitalist approach to the business of computer development, one in which companies incorporate to produce goods and are profitably renumerated for their labour and investment. Interestingly, it is Gates the realist profiteer who has emerged from among the early computer pioneers as the most effective philanthropist, the one who has dedicated his wealth to the common good in the form of poverty relief initiatives, vaccine programmes, and climate research. For his trouble, he has become the target of inane conspiracies in direct lineage of those promulgated by the libertarian hippies and counterculturalists of the ‘60s and ‘70s (although it must be said that the picture is mixed - as highlighted by anti-trust suits in the 1990s, Microsoft has also been a force for monopolisation and control).

And what of Fred Moore’s anti-money utopianism? A year before Gates drafted his letter Moore had already left California, having concluded that his Homebrew club would be an incubator of entrepreneurialism, rather than world peace. The violent sound of snapping was audible, as the contradictions piled up on the fragile corpus of personal computer idealism. John Markoff in What The Doormouse Said:

At every opportunity [Moore] repeated his mantra of sharing. But the entrepreneurial explosion that he had touched off was unstoppable…He had been deeply frustrated by the corrosive power of money and then overnight had helped create a powerful community in which the free sharing of information was not just an aspect of it but the essential reason for its existence. The deep irony was that Fred Moore lit the spark that burned brightly in two contradictory directions – towards the creation of powerful information tools that made information remarkably easy to share and increasingly valuable at the same time.

The Homebrew Computer Club was fated to change the world, but when the change came, it was not the one Moore had hoped for. The Homebrew Computer Club wound up serving as the catalyst for what venture capitalist John Doerr was to call ‘the largest legal accumulation of money in history’. At least twenty-three companies, including Apple Computer, were to trace their lineage directly to Homebrew…the hobbyists would tear down the glass-house computing world and transform themselves into a movement that emphasized an entirely new set of values from traditional American businesses.”

The “change that Moore had hoped for” did not arrive precisely because the genesis of the personal computer was not motivated by any genuine, coherent social-political mission, but simply an anamorphous set of mantras around “individualism” and “liberty”.

What we see from the Libertarian-Capitalists’ alternative vision of a devolved, distributed counterculture of unregulated, free exploration, hacking and piracy, is that, for many, it extended only as far as it suited their personal interests. This was of-a-piece with the ideologies at work in the religious side of the Counterculture during the 1960s. Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak’s iconoclasm, their production and sale of Blue Boxes with which to hack the telephone network, their chatter about “decentralisation” and “liberty”, all of this was profaned by the giant, centralising corporation that they were happy to build; one which now shakes-down small independent artists for 30% of the donations pledged to support those artists via Patreon, and spends three times on patents and lawsuits the sum that it commits to R&D. The same is true for many of the other evangelists for small, non-hierarchical enterprises that ended up running giant corporations that are more powerful than the IBMs of the world ever were. Much of the techno-hippie talk about the free-flow of information can be simply attributed to a selfish desire to do as one pleases without the inconvenience of restriction and regulation. As John Markoff phrased it, “Silicon Valley has long been motivated by what author Michael Malone called “The Big Score” – more simply put, greed”.

These tendencies can be observed in each new advance or epoch that erupts from Silicon Valley, one is currently raging about us: the AI revolution. In fealty to the Valley’s laissez-faire approach to everyone else’s rights, even while it litigiously enforces its own, the AI companies are happily exploiting, libre and gratis, the combined fruits of mankind’s artistry, wisdom, intellect and labour in order to train its models, and has no intention of paying for the privilege. It has also (again) embarked on an absurdist demolition of formerly productive industries, in furtherance of an unguided, energy-intensive chaos-engine that has nothing to say about what will adequately replace the economies that it collapses. The technology companies have adopted the Homebrew approach only in a limited way: as a stalking horse for constructing profit-extracting monopolies and cartels later.

Silicon Valley has managed to synthesise the two, opposing propositions in Bill Gates’s dispute with the Homebrew Computer Club: a radical form of the proprietary protectionism defended by Gates, and the Homebrewers’ ethic of “free” – which is little more than John Perry Barlow’s “giving it away” deployed as a tactic until the market collapses and the protectionist oligarchy can emerge. This is the logic of “disruption”, a destructive form of Libertarian Capitalism which produces unaccountable monopolies and centralised power.

The venture capital model pioneered by Arthur Rock, which venerates charismatic individuals, which emphasises empire and dominance, has cultivated enterprises that, unencumbered by the need to grow modestly with the goal of incremental profitability, are in consequence egotistical, megalomaniacal.

This is what happened when Libertarian ideologies in the counterculture reconciled with capital, it really was “the next thing after acid”: many of the leaders of the New Left became venture capitalists; Black Panthers, hippies, Merry Pranksters all flooded into the Republican Party, where they worked to bring about Ronald Reagan’s Neoliberal age, an immaculate political expression of the amoral concept of freedom that attended acid, the hippies and the Hell’s Angels.

John Markoff published What The Doormouse Said in 2004. Twenty years later, one of his final passages has proved to be remarkably prescient:

The computer hackers’ urge to share and the entrepreneurs desire for wealth – it is a confrontation that will inevitably define new technology revolutions. The stage is set for a clash of values that echo the various forces that created Silicon Valley.

What is interesting about Markoff’s portent, is that the clashes he foresees between the “urge to share” and the “desire for wealth” have to a large extent been reconciled by the next phase in the techno-hippie dream: the free flow of information in cyberspace, distributed networks liberated from the supervision of governments and the control of old systems of repressive power.

Those networks bequeathed us Social Media, which has managed to convert the urge share into a source of massive wealth.