Techno-Fascism Part#4: Virtual Freedom

The Network & the political economy of Cyberspace

Our generation proved in cyberspace that where self-reliance leads, resilience follows, and where generosity leads, prosperity follows. If that dynamic continues, and everything so far suggests that it will, then the information age will bear the distinctive mark of the countercultural '60s well into the new millennium.

— Stewart Brand, We Owe It All To The Hippies, Time Magazine, Volume 145, Number 12 1st of March, 1995

We will create a civilization of the Mind in Cyberspace. May it be more humane and fair than the world your governments have made before.

— John Perry Barlow, A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace, 8th of February, 1996

The 1990s

In history’s halcyon end days, with the dark Satanic mills abandoned, collapsed and cleared, the chewing gears and raging foundries still and cold, and the iron curtain lowered, money ticked over. It travelled through the networked markets tended by benign and rational motherboards that blinked away at the end of the gold-brick road, under the gleaming spires of the Silicon City, where the clouds drifted across infinite glass, the sky repeated in mirrored facades, and the impression was one of floating through air, blessed by heat of the sun.

The politics of self-interest, that had always been implicit in the countercultural ‘60s, were, by the ‘90s, explicit. Many on the radical Left had embraced Reagan-era Capitalism, in some cases working for the Reagan and Bush administrations, or right-wing Republican politicians, or evangelical Libertarian-Capitalists. Jerry Rubin, the former radical Leftist leader of the Yippies and one of the Chicago Seven, said “the strategy of this generation is to transform America through entrepreneurial Capitalism…we’ve learned that the alternative to Capitalism doesn’t allow much freedom and we’re in the process of transforming Capitalism from big business to entrepreneurship”. Rennie Davis, one of the leaders of Students for a Democratic Society, and another of the Chicago Seven, became a venture capitalist with an emphasis on tech investments, as well as a self-absorbed mystic and advocate for daft New Age Spiritualism.

The start-ups and tech enterprises awash with venture capital riches named themselves after Ayn Rand and various of the deranged hallucinations in her books; some of their executives even named their children after various of the deranged hallucinations in her books. Rand’s philosophy of selfishness was by now openly venerated by the techno-hippies and their descendants. Forget Socialism, equality, liberty from the exploitation of capital and the other naïve, repressive illusions of the New Left – the liberated future would belong to the entrepreneurial individual, and it would be non-exploitative spiritually. The Golden Rule, “do no harm”, best intentions.

The era of the personal computer which the techno-hippies promised would liberate the individual from the asphyxiating grip of The Man, and enable him to pursue his own self-interest, had arrived. It was of course intimately entwined with the arrival of another technology that had been rapidly progressing since the 1960s: the network.

The network had its origins in the cybernetic visions of the computer savants: Vannevar Bush’s vision of the Memex, J.C.R Licklider’s concepts of “man-computer symbiosis” and the latter’s work on time-sharing; all of which we explored in Part 2 of this series.

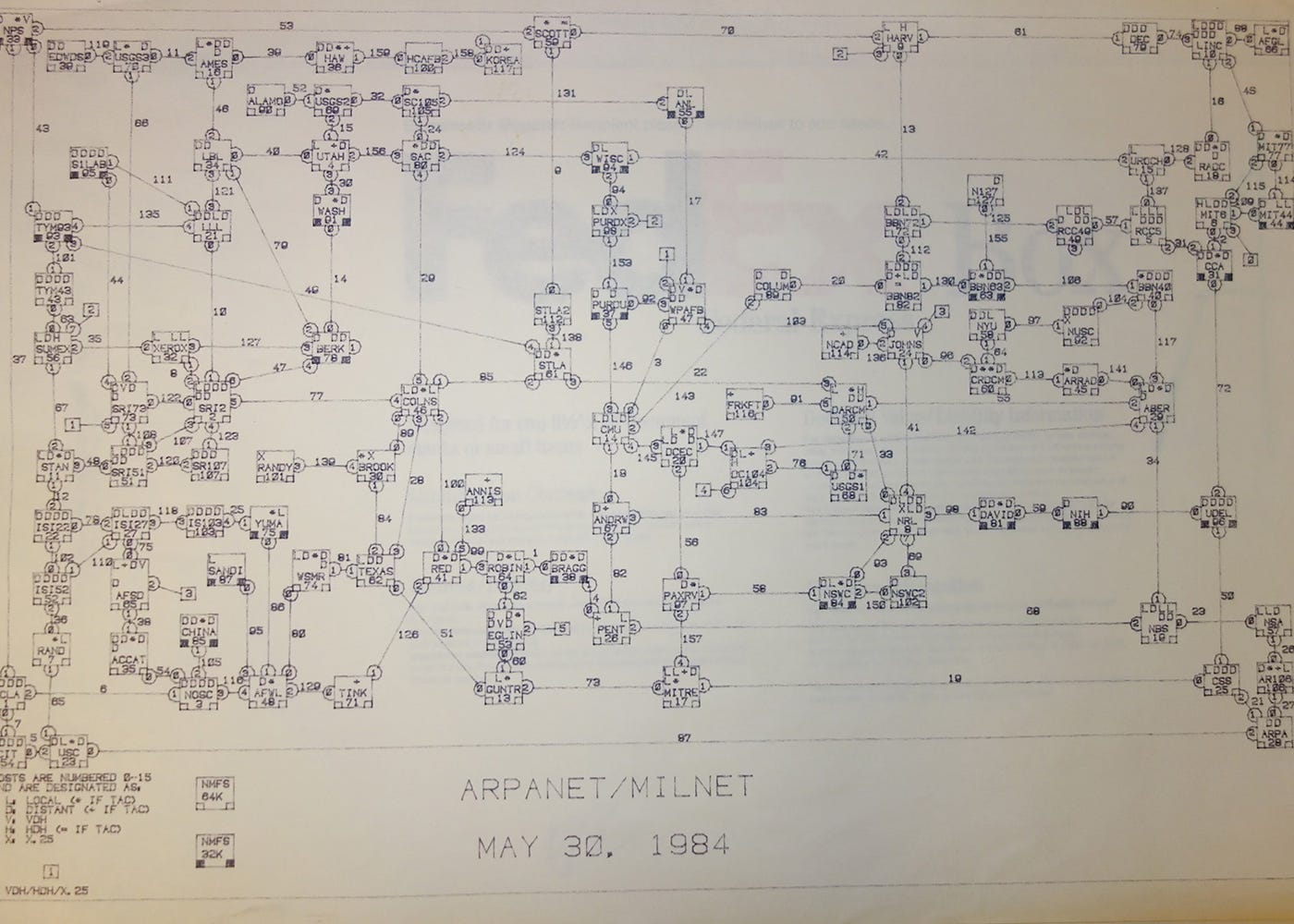

In 1962, Licklider pitched up at the Pentagon’s “Advanced Research Projects Agency”, or “ARPA”, where he began articulating grand concepts for an “intergalactic computer network”, with centres that are “netted together” globally. These ideas translated into the development of ARPANET, the precursor to the modern internet.

The foundation stone of ARPANET was that it would be a fully distributed network. This principle, established at its genesis, is absolutely fundamental to our understanding of the internet and how it operates. It meant that, unlike a centralised network, with a single controlling hub, or a decentralised network, with a series of regional hubs, ARPANET, and thus the internet, would comprise a network of nodes, equal in their ability to distribute data, a system that would empower individuals and over which it would be difficult, even impossible, to exercise central control.

This design was in part motivated by security concerns, the project was being paid for by the Pentagon, after all. In a centralised or decentralised system, an enemy attack on the central command or regional hubs - say, a nuclear strike – could take down the entire network. With a distributed system, it would be impossible to eliminate all the nodes, any that became incapacitated would have their data routed through alternatives, the network would always continue to function.

In the 1980s, as modems became widely available, this cyber-utopian dream of an emancipated network, a “liberated zone” like Haight-Ashbury and the countercultural hubs of the ‘60s, synthesised with the techno-hippies’ vision for the personal computer as an instrument with which to extend the capacity and independence of individuals. Personal computer users would be able to build communities in cyberspace, liberated zones impervious to the supervision and demands of authority; unlike in the ‘60s, The Man would not be able to deploy the National Guard.

Again Stewart Brand appeared, like Merlin under an electrical storm, approaching once more from over the misty hills to anoint the arrival of a new computing age and announce the risen sun. This time it would be the reincarnation of his Whole Earth Catalog as the Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link, or WELL, arguably the first ever virtual community, and a precursor to modern social networks.

Established in 1985, the WELL aimed to be an egalitarian, non-hierarchical community defined by its members. People were free to discuss anything that they wished, new users were greeted with the phrase “You Own Your Words”, which was both a dispensation and a warning – your contributions to the WELL would not be commodified or copyrighted, but you also bear responsibility for your own actions. Both these principles would eventually be discarded by social media, in its avarice and exceptionalism, along with the nudge mechanism introduced to defend them: users on the WELL could not post anonymously.

A year or so after the WELL went live, its community was joined by John Perry Barlow, a counterculturalist, contrarian and polymath in the lineage of Ken Kesey, who was closely associated with the Grateful Dead, having attended school with Dead guitarist Bob Weir and contributed lyrics to some of the band’s recordings. The WELL had a strong “Deadhead” presence, and Barlow became a prominent member, eventually joining its board of directors.

Barlow proved to be an energetic futurist, and travelled the world evangelising for the internet, while indefatigably filing articles and essays in praise of the coming cyber age. His utopian faith in the potential of cyberspace was profoundly ideological, animated by libertarian beliefs that he shared with figures like Kesey and Stewart Brand and which were characteristic of the discourse on the WELL. These are political views which, to my mind and for reasons that I discussed in Lessons from the Counterculture, place Barlow, contrary to his countercultural appearances, emphatically on the radical Right.

His formal political record justifies such a designation, despite various later recantations, apologies and caveats: he was chairman of his hometown Republican Party and ran Dick Cheney’s congressional campaign in 1968, only with the cursed birth of Donald Trump’s Presidency did he finally renounce the Republican Party and even then, as we shall see, with none of the self-awareness that becomes the true penitent.

Libertarianism and individualism of the Brand-Barlow variety was the dominant political mode of the WELL and other early internet communities. Usenet groups, discussion boards and mailing lists dedicated to advancing decentralisation, autonomy, and freedom from authority proliferated across the network. Many of these communities were either run or joined by people who would go on to become famous personalities in the cyber age – Julian Assange, for example.

In 1990 John Perry Barlow and two other Libertarians from the WELL, John Gilmore and Mitch Kapor, founded the Electronic Frontier Foundation, as an organisation aimed at “defending civil liberties in the digital world” and “to ensure that technology supports freedom, justice, and innovation for all people of the world”; they were later joined by Steve Wozniak, the co-founder of Apple. Their mission to oppose unjust control and subjugation of the network by traditional sectors of power was, on the face of it, a noble calling.

The Big Bang occurred in 1993, when Al Gore achieved success in his campaign to have the internet opened to commercial use. Cyberspace rapidly expanded, with new galaxies and star systems forming monthly. At the beginning of ’93 there were 50 web servers in the world, by the end of the year there were 500. Barlow and his fellow utopians space-walked in tearful wonderment, it really was the next thing after acid.

In ’96 a poetically moved Barlow, outraged by what he perceived to be a government/corporate attempt to colonise cyberspace, published A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace. “Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind”, Barlow intoned, “on behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. You have no sovereignty where we gather”. He went on to describe his vision for an anarchistic, self-regulating, supranational community, the ethical core of which would be the very Randian-sounding “enlightened self-interest”:

We have no elected government, nor are we likely to have one, so I address you with no greater authority than that with which liberty itself always speaks. I declare the global social space we are building to be naturally independent of the tyrannies you seek to impose on us. You have no moral right to rule us nor do you possess any methods of enforcement we have true reason to fear.

Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed. You have neither solicited nor received ours. We did not invite you… You do not know our culture, our ethics, or the unwritten codes that already provide our society more order than could be obtained by any of your impositions.

You claim there are problems among us that you need to solve. You use this claim as an excuse to invade our precincts. Many of these problems don't exist. Where there are real conflicts, where there are wrongs, we will identify them and address them by our means. We are forming our own Social Contract. This governance will arise according to the conditions of our world, not yours… We believe that from ethics, enlightened self-interest, and the commonweal, our governance will emerge. Our identities may be distributed across many of your jurisdictions. The only law that all our constituent cultures would generally recognize is the Golden Rule. We hope we will be able to build our particular solutions on that basis. But we cannot accept the solutions you are attempting to impose.

Quite apart from the astonishing hubris on display in presuming to speak for every internet user, which would, in short order, be pretty much the entire world, Barlow’s declaration was, of course, hopelessly naïve. On what premise did he hold the belief that all internet users would “recognize the golden rule”? With what mechanisms did he propose to “identify and address real conflicts and wrongs”, and who appointed him to do so, by the way? The strong impression is that, far from being a thoughtful response to nascent issues of governance, jurisdiction and regulation of the internet, Barlow’s declaration was simply a statement that he preferred to do just as he liked, without reference to anyone or anything else, thank you very much. And wasn’t it always thus with the hippies, and their Libertarian apologia?

A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace was spectacularly successful, and inspired a corpus of works dedicated to Utopian futurism around the internet: hierarchies would vanish, the wisdom of crowds would construct balanced societies, citizen journalism and user-generated content would secure the accuracy and integrity of information.

In his documentaries All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace and Hypernormalisation, Adam Curtis describes the Brand-Barlow vision as one in which “individuals freed from political control and hierarchies find themselves in a network with its own equilibrium and natural order…a new, powerful individualism that could not fit with the idea of collective political action”

On one level, the computer revolution framed in this way was a means of grappling with the pure id of a hippie movement that had ended the 1960s with the Weathermen and domestic terrorism. It posited a system based on rationalism and logic, and which would achieve “equilibrium”, objectivity, the Golden Rule; and which could mitigate some of the worst excesses of the extreme solipsism and selfishness previously unleashed by the syncretic Libertarianism, Leftist radicalism and identity politics of the counterculture, without discarding the Libertarianism and individualism. “Computers would liberate society”, Stewart Brand said, “power to the people in a very direct sense. An eco-system that was self-correcting”.

“Barlow gave a picture of cyberspace not as a network controlled by corporations, but as a magical free place”, Curtis says in Hypernormalisation, “an alternative to the old systems of power. It was a vision that came to dominate the internet over the next 20 years… a place that they could retreat to, away from the harsh right-wing politics of Reagan’s America”.

For Curtis, this ambition is a fallacy. He points out that in the 1960s communes, supposedly non-hierarchal communities of free individuals, leaders inevitably emerged. The egalitarian dream of the communes in California, which inspired Engelbart and the personal computers, ended up creating hierarchical structures. “The self-organising model”, Curtis argues, “cannot deal with the central dynamic forces of human societies – politics and power…The networks hadn’t eliminated power, they had just shifted it, and concentrated it in new forms”.

While I largely agree with Curtis’s analysis, there is often a fatalistic, even nihilistic, streak that runs through his work that I think, in this case, leads him to be too generous towards the cyber-utopians and techno-hippies. For Curtis, capital and power are inexorable and never really change; the techno-hippies are just benign, utopian fantasists recoiling from the truth.

Where I depart from Curtis, is that I don’t think that the cyber-utopians were looking for “a place that they could retreat to, away from the harsh right-wing politics of Reagan’s America”, I think that they actively colluded in those politics. Reagan’s deregulating, privatising, marketizing, tax-cutting government chimed melodically with their hippie Libertarianism, inherited from the Merry Pranksters, and their affinity with Ayn Rand’s “heroic individual” and William Rees-Mogg’s “Sovereign Individual” (a new right-wing fantasy birthed in the 1990s, which would come to be heavily influential amongst the techno-fascists and billionaire plutocrats of late Silicon Valley - Peter Thiel contributes the introduction to the latest edition). Reagan’s America was Jerry Rubin’s “entrepreneurial Capitalism” and Stewart Brand’s veneration of business, the spirit and philosophy of which they carried into the 1990s.

In the early ‘90s John Perry Barlow staged “Cyberthons”, gatherings of cyber-utopians through which he tried to build a movement. “The Cyberthon as it was originally conceived was supposed to be the “90s equivalent of the Acid Test”, Barlow said, “and we had thought to involve some of the same personnel…and it immediately acquired a commercial quality that was initially a little unsettling to people like me but as soon as I saw it actually working I thought ‘ah, well, if you’re gonna have an Acid Test for the ‘90s money better be involved’”.

If there was anything that Barlow and his cyber-utopians wanted to “retreat” from, it was not the “harsh right-wing politics” of Reaganism, as Curtis would have it, it was the logic, the material realities and hypocrisies of their own politics. Their utopianism wasn’t an attempt to escape their ideological ally Ronald Reagan, it was an effort to escape themselves, to escape accountability.

Brand and Barlow’s aphorisms – “information wants to be free and it wants to be expensive”, “the best way to raise demand for your product is to give it away” – show that they were aware of the paradoxes that entwined their political views, but it was as if they were content simply to observe these paradoxes: curiosities, part of an inconsequential, discursive game. The networked computer age financed by venture capital and centred in the Silicon City, however, was amassing enormous economic, social, and therefore political, power. The way that these technologies integrated into societies was not a utopian game or thought experiment, it was a deadly serious historical inflection point, and arguing that it should be premised on laissez-faire Capitalism and shallow, hippie Libertarianism would have consequences.

John Perry Barlow did experience some blowback in the early online communities. Hypernormalisation examines “a notorious public debate online, [in which] two hackers attacked Barlow. What infuriated them most was Barlow’s insistence that there were no hierarchies, or controlling powers, in the new cyberworld”. The hackers stole Barlow’s credit data and published it online, they wanted to demonstrate that, contrary to Barlow’s fantasies, the internet was a technology which enabled sectors of power to gather previously unheard-of levels of detail about individuals, which could then be used to coerce and manipulate. In All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace, Curtis highlights the case of a woman who posted on one of the early chat boards and who had come to the realisation that, in participating in Cyberspace, she had commodified herself and her interior thoughts, that Cyberspace was “a black hole that takes human emotions and reproduces them as spectacle”.

A few months after John Perry Barlow posted A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace online, the technology writer Paulina Borsook published Cyberselfish in Mother Jones Magazine. Cyberselfish was both an account of Borsook’s time in Silicon Valley, and a critique of its politics which were, at that time, generally obscure to the public. She coined a new, catch-all term to describe the community of techno-hippies and cyber-utopians: “technolibertarians”. “It came as a shock, when I stumbled into the culture of Silicon Valley”, Borsook wrote, “although the technologists I encountered there were the liberals on social issues I would have expected (pro-choice, as far as abortion; pro-diversity, as far as domestic partner benefits; inclined to sanction the occasional use of recreational drugs), they were violently lacking in compassion, ravingly anti-government, and tremendously opposed to regulation”. She went on to present an excoriating depiction of technolibertarianism, in its hypocrisy, and in its virulently right-wing ideology excepting, of course, the cosmetic approval of joints and gay sex:

These are the inheritors of the greatest government subsidy of technology and expansion in technical education the planet has ever seen; and, like the ungrateful adolescent offspring of immigrants who have made it in the new country, they take for granted the richness of the environment in which they have flourished, and resent the hell out of the constraints that bind them. And, like privileged, spoiled teenagers everywhere, they haven’t a clue what their existence would be like without the bounty showered on them. These high-tech libertarians believe the private sector can do everything — but, of course, R&D is something that cannot by any short-term measurement meet the test of the marketplace, the libertarians’ measure of all things. They decry regulation–except without it, there would be no mechanism to ensure profit from intellectual property, without which entrepreneurs would not get their payoffs, nor would there be equitable marketplaces in which to make their sales…. And when Self magazine started an online gun control conference on The WELL, an electronic bulletin board and Internet gateway smack in the middle of tree-hugging, bleeding-heart-liberal, secular-humanist Northern California, opinions ranged from mildly to rabidly anti-gun control…The nexus of libertarianism and high-tech in the Silicon Valley will come to matter more and more, because it involves lots and lots of money.

Borsook’s conclusion was stunning in its perspicacity and prescience:

As surely as power follows wealth, those who make money decide that society, having rewarded their random combination of brains and luck in one sphere, should pay attention to them in another. And so, high-technocrats are beginning to try to influence the world beyond VDTs [video display terminals].

But what will result if the people who want to shape public policy know nothing about history or political science or, most importantly, how to interact with other humans? Programmers, and those who know how to make money off them, mostly find it easier to interact in e-mail than IRL (in real life), and are often not good at picking up the cues, commonplaces, and patterns of being that civilians use to communicate, connect, and operate in groups.

The convergence between libertarianism and high-tech has created the true revenge of the nerds: Those whose greatest strengths have not been the comprehension of social systems, appreciation of the humanities, or acquaintance with history, politics, and economics have started shaping public policy. Armed with new money and new celebrity — juice — they can wreak vengeance on those by whom they have felt diminished.

We began with a quote from Stewart Brand’s 1995 article in Time Magazine: “the information age will bear the distinctive mark of the countercultural '60s well into the new millennium”. In that prediction he was correct. The technolibertarians dragged the Starbucks Paradox out of Haight-Ashbury and into the networked era, which evolved in context of Capitalism and in particular Venture Capitalism and, even more specifically, the neoliberal Capitalism inaugurated in the Reagan era. They were so keen that life should proceed according to their utopian visions, that they ignored how it was likely to proceed. They did not take into account the mechanics of power, which they perceived, in the unsophisticated, conspiratorial hippie’s way, as simply the dictatorship of The Man. In that sense they made a false distinction between the coercive state and its institutions, and private companies which, within their cosmology, are something akin to community associations of free individuals, operating in free markets. What this limited analysis misunderstands is the dynamics of power, and that the power of private interests can be just as coercive, if not more so, than that of the state, with none of the mechanisms of accountability. Technologies, just as psychedelic drugs or decent rock music, do not fundamentally alter power dynamics. As the ‘60s should already have shown them, hierarchies always emerge, the question is one of accountability, which is political.

The technolibertarians wilfully refused to parse their ideological contradictions - the contradictions highlighted by the hackers who stole John Perry Barlow’s data to make a point, the contradictions essayed by Paulina Borsook in her five-alarm warning, the contradiction between Steve Wozniak’s place on the board of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, while Apple Computer aggressively constructs monopolies, files and enforces patents, extorts independent artists, golden rule be damned.

The figure who was prepared to be honest about these contradictions, was the Moses of neoliberal Capitalism, Milton Friedman. Friedman’s ideas shaped the economic context of the technological age, applied the philosophies of Ayn Rand, bequeathed Reagan his programme and expressed the beliefs of the technolibertarians, as seen directly in John Perry Barlow’s eager sponsorship of the garrulous Conservative politician and Friedmanite Dick Cheney; “the smartest man I’ve met”, Barlow fawned of Cheney.

In 1996, the same year that Barlow published A Declaration and Borsook Cyberselfish, Milton Freidman gave an interview in which he said:

Hong Kong in political terms has been a dictatorship, but it’s been a benevolent dictatorship. It had a completely laissez-faire economic policy…there is almost no doubt that if you had political freedom in Honk Kong you would have much less economic and civil freedom than you do as a result of an authoritarian government…I believe a relatively free economy is a necessary condition for freedom, but there is evidence that a democratic society, once established, destroys a free economy.

What Friedman doesn’t appear to have contemplated quite so thoroughly, is whether his particular notion of a “free economy” might, in fact, destroy democratic societies. In February 2025, a few weeks after snapping out his notorious Nazi salute, Elon Musk approvingly tweeted a video of Milton Friedman advocating the abolition of almost all the democratic institutions of the state. “Milton Friedman was spot on”, he captioned it. We have since seen the yield of Musk’s evisceration of the US Federal Government, a grotesque performance in which he appeared before cameras and gleefully wielded a growling chainsaw. The consequences of his cuts to USAID are estimated, by the Lancet, to include one million avoidable HIV infections amongst children, with half a million of those children expected to die from AIDS within the next five years. The World Food Program has predicted a crisis of starvation, malnutrition and insanitary drinking water.

Time has proved that Freidman’s Libertarian economics, and the ideologies advocated by technolibertarians, have been spectacularly adept at launching massive transfers of wealth to the rich, hollowing out democracies and collapsing economies. In 1997, a year after he gave his interview in praise of Hong Kong’s “completely laissez-faire economic policy”, Hong Kong’s economy crumbled in the Asian Financial Crisis; it had to be bailed out by massive state intervention. This pattern has repeated throughout the neoliberal era, with expansive implications for the political health of societies. In the next part of this series I’ll look at two cases in particular: Japan in 1990, and the great crash of 2008.

The consequences of neoliberal collapses would in turn feed back into the technological age, the aftershocks speeding through the cables and circuit boards, back towards the Silicon City. “The distinctive mark of the countercultural '60s” was indeed coming for the new millennium, but not in the way that Brand imagined: its venture capital; its Libertarianism; the individualism that had produced the personal computer; the conspiratorial distrust of government that had produced the distributed internet; its utopianism and cultishness, which wilfully refused to acknowledge the darkness that gathered at the edges of its sun-kissed towers.

In the last, from all the circuits tangled with contradictions, we have the grand contradiction articulated by the philosopher Slavoj Žižek: “Maybe you accentuate in a wrong way the radical untouchable character of personal freedom, individual freedom. Brought to the end this attitude is self-destructive, because too much individual freedom…destroys human freedom itself”.