Techno-Fascism Part#5: A Modern Weimar

“The best way to raise demand for your product is to give it away.”

-John Perry Barlow, The Economy of Ideas, 1994.

Japan, 1990: an asset bubble produced by financial liberalisation explodes, the fireworks can be seen streaking across Pacific skies, a glittering spectacle of extinguished hope, the descending sparks fading into the lightless night, where misery, despair and bitterness will reign in Japan’s “lost decade”. This was the yield of the kind of policies advocated by libertarian free-marketeers in Silicon Valley, by cyber-utopians like John Perry Barlow, by their political allies, like Dick Cheney.

The lost decade saw the dank fog of economic depression swallow Japan. The youth became the primary victims of a broken social contract, employment opportunities were limited, an early iteration of the gig economy appeared – low paid, unstable and short-term work, not a foundation on which to build a life.

Despair descended. Japanese suicide rates climbed to the highest ever seen in the developed world. Japanese youth, economically trapped in the parental home, locked themselves in their bedrooms, comforted only by the faint blue glow of their computer screens, and the seductive fantasy worlds out in cyberspace, where new subcultures emerged from the gloom.

In 1999 Hiroyuki Nishimura, a Japanese student living in Arkansas, created a bulletin board which catered to online communities and subcultures in Japan, he called it 2channel. Unlike Stewart Brand’s WELL, 2channel permitted users to remain unregistered, anonymous, and to post using the default handle “nameless”. A type of nameless user became ubiquitous on 2channel: the “Otaku”, or “Superfan”. These were obsessive fans of anime and Japanese pop-culture from amongst the disenfranchised, ultra-online youth, who used 2channel to create their own virtual communities.

Uninhibited by the fear of social stigma or reproval, the anonymous denizens of Otaku communities on 2channel began to articulate the type of political ideology which is always attractive to the disempowered, the hopeless, the lonely, the bitter and angry: right-wing nationalism. These posters became known as “Netto Uyoku”, or “net-rightists”, their politics were the typical populist-right mix of nationalism, revanchism, and atavistic normativity (“things were better in the past when traditional values reigned”). They denied the historical crimes of Imperial Japan and venerated its legacy, they expressed violent xenophobic hostility towards perceived enemy civilizations (China, Korea), and their disposition was one that we have become all too familiar with in the social media era: vengeful, conspiratorial, hostile to offline communities and sources of information (the “mainstream media”, the “elites”), petty and volatile. With virtual communities a poor substitute for actual human social contact, all that these net-rightists, isolated behind their computers, really had as a source of identity and meaning, beyond their pop-culture obsessions, was that they were Japanese, a concept in which they invested, and defended to the last. Make Japan great again.

In 2003, Chris Poole, a fifteen-year-old American, fan of Japanese anime and regular visitor to the forum Anime Death Tentacle Rape Whorehouse on the website Something Awful, began to notice that much of the content shared on the forum had originated elsewhere, on a Japanese board called Futaba Channel, a place that 2channel users had migrated to when the latter had been threatened with closure.

Poole decided to download Futaba Channel’s open-source code and make an English-language clone of it for a Western audience, in the process, the default user handle “nameless” was incorrectly translated as “anonymous”, which in turn became the default username on Poole’s creation, 4chan, and its infamous original board: /b/ (Anime/Random).

4chan, and in particular /b/ board, started as a place for outrageous, iconoclastic humour and pranks, anti-establishment counterculturalism and grassroots cyber-activism – the hacktivist collective “Anonymous” was born on /b/, and named after the default handle of its users. Echoing the cyber-utopian dreams of John Perry Barlow, Poole gave an interview to the New York Times in which he said, “the power lies in the community to dictate its own standards”. 4chan would not be centrally policed or moderated, there was no hierarchy, the community would self-regulate, free from censorship.

Although it hosted a certain strain of iconoclastic humour that wasn’t to be taken absolutely seriously, 4chan soon went the way of its Japanese predecessors and descended into racism, nationalism, conspiracy theories and extreme, reactionary identity politics. “Net-rightism” became the political characteristic of a section of 4chan users who, shielded by the anonymity that was forbidden on the WELL, never had to face accountability for their words and deeds. An ugly form of transgressive fascism began to germinate on 4chan, from where it spread to other online communities of disaffected, or simply bored, youth.

Web 2.0 and the cyber surveillance state

A year after the appearance of 4chan, the very first Web 2.0 conference was held in San Francisco, the era of the social network had arrived. In contrast to the first generation of websites, on which users passively viewed content, web 2.0 emphasised user-generated content and a participatory culture in much the same way as the cyber utopians of the WELL had envisaged. Web 2.0 would create borderless cyber kingdoms ruled by their citizens according to the principle of the “golden rule”, with agency devolved to the individual user, rather than preserved in the mediating hands of corporate webmasters, the promise of the fully distributed internet finally fulfilled.

Between 2004 and 2006 Facebook, YouTube and Twitter were all founded, financed by the Silicon Valley venture capitalists that established their business model with Fairchild Semi-conductor back in the fifties (and which we looked at in part three of this series), although by now the business model had mutated.

John Perry Barlow’s 1994 essay The Economy of Ideas attempted to address issues around what digitisation would mean for property rights, and for the ability of creators to be recognised and rewarded for their work. As was typical, Barlow’s most pressing concern was his idealised concept of liberty (“the greatest constraint on your future liberties may come not from government but from corporate legal departments laboring to protect by force what can no longer be protected by practical efficiency or general social consent”), and while on one level the essay is thoughtful and sober, even prophetic, it’s also hopelessly naïve and utopian, “I believe that the failure of law will almost certainly result in a compensating re-emergence of ethics as the ordering template of society”, Barlow declared, while he recycled his evidence-free belief that communities of liberated individuals will somehow consensually produce equitable societies.

In The Economy of Ideas Barlow reached for an example from his time working with the Grateful Dead. He explained how the band had expanded its popularity by encouraging fans to make bootleg recordings of their concerts, “the best way to raise demand for your product”, Barlow wrote, “is to give it away”, and it was a form of this theory that Silicon Valley venture capitalists deployed as the economic premise for the design of web 2.0.

YouTube, Facebook and the other web 2.0 companies appeared to offer a free product, but in reality they were exploiting the “free labour” of user created content while venture capital underwrote massive financial losses. Web 2.0 Terms of Service agreements were very happy to take advantage of Barlow’s “outdated” concepts of law to claim perpetual licenses to user-generated content. In turn, they used that content to create profiles of users to sell to marketers, precisely the commodification of private individuals and their thoughts that some users of the early internet chat groups had feared. Web 2.0 sites, it became clear, were involved in a type of giant surveillance operation against their users, precisely the opposite of what the cyber-utopians had envisaged. Constantly retaining and engaging their users became of paramount importance to the business plans of the social networks, and they eagerly developed algorithms that would do just that.

Disruption salts the earth

Meanwhile, out in the real economy, a version of this logic was busily dismantling previously thriving industries through the process Silicon Valley euphemistically terms “disruption”. What “disruption” means in practice is that tech companies, backed by apparently inexhaustible venture capital, parasitically enter a host market, deploy the Barlow principle, and leech all the value from that market until the market is either no longer viable, its businesses reduced to brittle, necrotic husks, or the tech companies have managed to construct an oligopoly. Think of it as the economic version of Invasion of the Body Snatchers. To be clear, this is not Capitalism, it actively disdains Capitalism’s core tenets that the business-of-business is to pursue honest profits and that fair competition is the key to effectively functioning markets.

Cyber-utopians were often derisive of any endeavours unrelated to technology, or where the economics might impede their vision of a techno-libertarian future, and dismissive of the rights of others to earn a living. “As we return to continuous information, we can expect the importance of authorship to diminish”, John Perry Barlow wrote in The Economy of Ideas, “Creative people may have to renew their acquaintance with humility”.

Paulina Borsook, in her 1996 article Cyberselfish, observed:

Implicit is their assumption that those who excel by working with the tangible and not the virtual (e.g., manufacturing and servicing actual stuff) are to be considered societally superfluous. Technolibertarians applaud the massive industrial dislocations taking place in affluent North America, comparable to the miseries of the Scottish enclosures or the Industrial Revolution.

It's worth taking a short detour at this point to examine how Silicon Valley’s Bodysnatchers operate in greater detail. The starkest example came during the Covid pandemic, when several prominent tech startups, including Deliveroo and Uber, suddenly ran into financial trouble. The companies started frantically shedding jobs, and like all Randian heroes who venture forth asking for nothing but the freedom to harvest the fruits of their own endeavour, they suddenly became committed socialists and begged for evil government bailouts.

These events were striking and incongruous: Deliveroo delivered food at a time when all restaurants and cafes were closed and supermarket visits were limited to one a day; Uber also delivered food, and provided private transport at a time when people were eager to avoid public transport. It should have been the glory years for both businesses, they should have been printing gold bullion, and hiring every out-of-work waiter and furloughed airline pilot who had no alternative but to accept their shitty pay and conditions. How could it be possible that the insolvency sirens were blaring? An article by James Ball, published in The Guardian in 2020 and headlined Deliveroo was the poster child for capitalism. It’s not looking so good now, gets us to the bottom of the matter:

The answer lies in the fact that Deliveroo’s real business model has almost nothing to do with making money from delivering food. Like pretty much every start-up of its sort, once you take all of the costs into account, Deliveroo loses money on every single delivery it makes, even after taking a big cut from the restaurant and a delivery fee from the customer. Uber, now more that a decade old, still loses money for every ride its service offers and every meal its couriers deliver.

In other words, drastically increasing sales sends the losses soaring. If your business is the business of losing money, the last thing that you need is more business. But why? Who would design such a deranged scheme, an inversion of Capitalist rationale? Ball explained:

This is the entire venture capital model – the financial model for Silicon Valley and the whole technology sector beyond it. Don’t worry about growing slowly and sustainably, don’t worry about profit, don’t worry about consequences. Just go flat out, hell for leather, and get as big as you can as fast as you can. It doesn’t matter that most companies will try and fail, provided a few succeed. Valuations will soar, the company will become publicly listed (a procedure known as an IPO) and then the company will either actually work out how to make profit – in which case, great – or by the time it’s clear it won’t, the venture capital funds have sold most of their stake at vast profits, and left regular investors holding the stock when the music stops.

Tech giants move in on existing sectors that previously supported millions of jobs and helped people make their livelihoods... They offer a new, subsidised alternative, that makes customers believe a service can be delivered much more cheaply… These start-ups come in to existing sectors essentially offering customers free money: £10 worth of stuff for a fiver. It turns out that’s easy to sell. But in the process, they rip the core out of existing businesses and reshape whole sectors of the economy in their image.

Invasion of the Bodysnatchers.

We’ve seen this dispiriting phenomenon deplete living standards over the past twenty-five years: industries that were once stable, solvent and provided decent careers were driven into insolvency by “disruptors” collapsing the profitability of their sectors. Workers found themselves accelerated into unstable, underpaid work in the gig economies; a joyless subsistence in service to the tech giants, as memorably depicted in the film Nomadland, for example. What eventually developed was a hybrid system of radical proprietary protectionism (in hypocritical opposition to the Libertarianism Silicon Valley likes to profess), combined with Barlow’s “giving it away for free”, until the market collapses and an oligarchy emerges.

But back in the early noughties, and the dawn of Web 2.0, those consequences remained obscure. A joyful spring planting was in progress, harvest time far away in other seasons. Inspired by the futuristic avant-garde out in Silicon Valley and their-fast moving economic deconstructionism (what is your limiting concept of maths, anyway?) grey-suit Capitalism on Wall Street embarked on a thrilling new era of disruption in the banking and real estate sectors…

The music stops for Neoliberalism

The World, 2008: an asset bubble produced by financial liberalisation explodes, the fireworks can be seen streaking across the sky, a glittering spectacle of extinguished hope, the descending sparks fading into the lightless night, where misery, despair and bitterness will reign. This was the yield of the kind of policies advocated by libertarian free-marketeers in Silicon Valley, by cyber-utopians like John Perry Barlow, by their political allies, like Dick Cheney.

With the 2008 financial crisis the neoliberal system that had driven globalisation since the 1980s collapsed. Either unwilling to be honest about that, or unable to conceive of an alternative, global institutions and political leadership resurrected that system in its zombie form. The social consequences matched those seen in Japan after 1990: life for most became more precarious and greater numbers of people retreated into online communities like 4chan, particularly the youth, who were often trapped in the parental home, and for whom prospects seemed especially limited.

Unlike previous recessions, the post-2008 malaise seemed depthless, fundamental. There was a sense that the whole social-economic system had not just broken, it had been revealed as a giant ruse, a malevolent fraud perpetrated on the majority by a narrow band of amoral liars who had extracted massive wealth and social capital at the expense of everyone else. New terms entered the lexicon with which to identify the guilty: “the 1%”, “the elites”, “the swamp”.

Social media became the locus of anti-establishment discourse and a tool with which to organise and co-ordinate protests. This was the apex dream of techno-hippies and cyber-utopians who had come of age in the counterculture of the 1960s; a distributed network in which non-hierarchical, mass-movements organised for social change without being vulnerable to attacks and infiltration from the establishment, nor subject to manipulation and betrayal by formal political leadership. It was Stewart Brand’s vision of “power to the people in a very direct sense”, in which “computers would liberate society”.

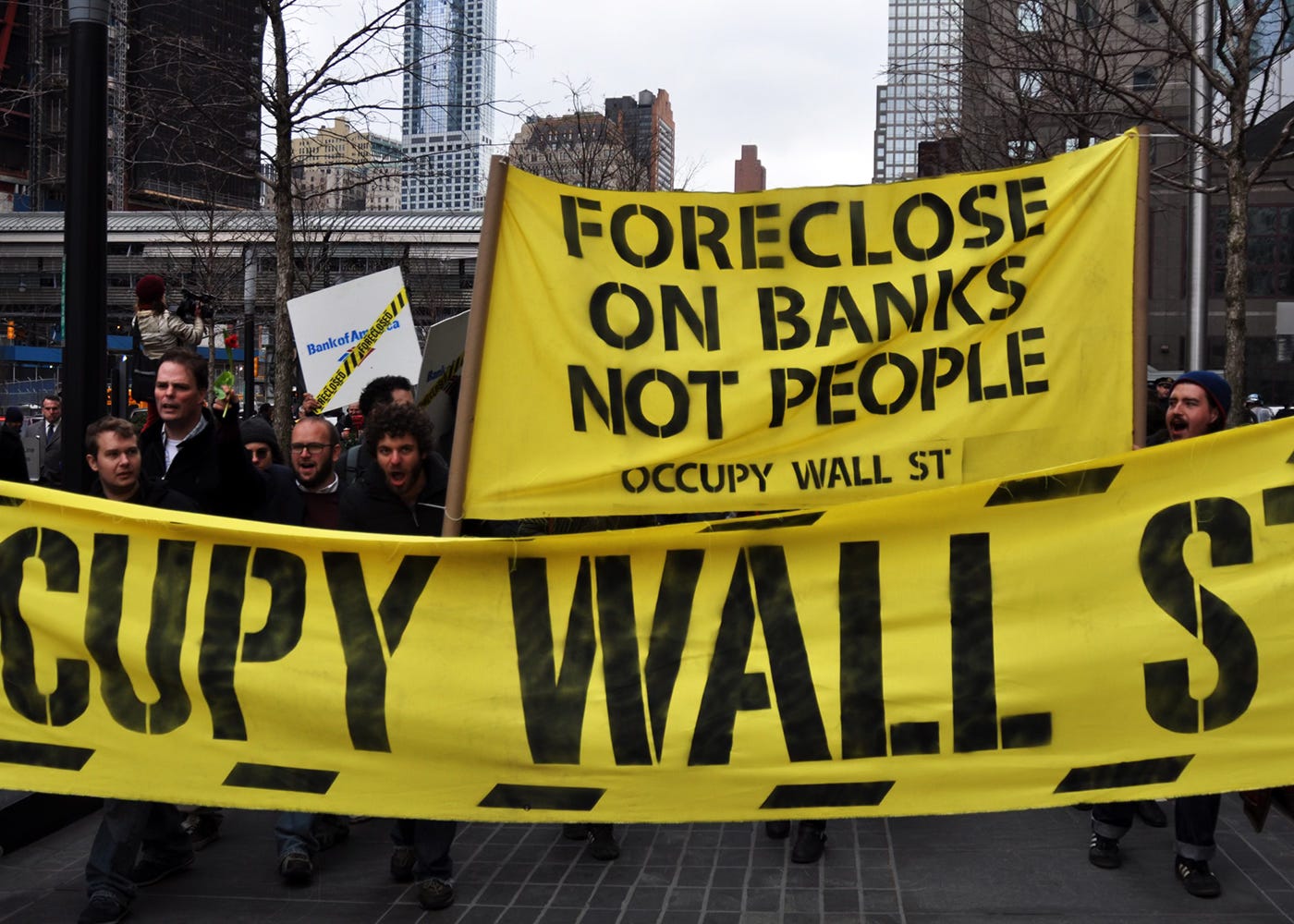

The most visible movement to emerge was Occupy, which explicitly modelled itself on the kinds of ideas articulated by John Perry Barlow, and staged worldwide protests, with the Guy Fawkes masks of 4-Chan’s Anonymous collective visible in the crowds. But, as Adam Curtis put it in Hypernormalisation:

It became clear that there was a terrible confusion at the heart of the movement. The radicals believed that if you could invent a new way of organising people, then a new society would emerge, but what they did not have was a picture of what that society would be like, a vision of the future. The truth was that their revolution was not about an idea, it was about how you managed things…. social media had helped to bring people together…[but] the internet gave no clue as to what kind of society they could create.

What was also interesting about the aftermath of the 2008 crash is that it resisted a critique of Capitalism. Movements like Occupy made some attempt, but were ultimately too rudderless and incoherent to successfully explain to people that what they were experiencing were the injustices, inequalities and crises that are produced by Capitalism. Instead, the majority interpreted the crisis in cultural, rather than economic, terms. The concept of “elite” became disassociated from economic power (billionaires like Donald Trump were not “elites”) and instead came to describe a perceived social power, enforced through culture, with the “mainstream media” complicit in the fraud through its role in cultural production.

On the liberal left, a traditional Socialist critique of Capitalism at its moment of crisis appeared to have been usurped by the belief in a redemptive “people power” and commitment to the individual. While more classic Socialist movements did spring up in Europe (Syriza in Greece, Podemos in Spain), in the US and, to an extent, the UK, the response was more in touch with the Libertarian-individualist ideas that had emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s; a programme of decentralised direct action and consumer action, and what amounted to the kind of Libertarian Capitalism that became the guiding ideology of techno-hippies and cyber-utopians in Silicon Valley and, ultimately, a powerful theme within online discourse.

That was an aimless road for the left, one which eventually forked off through the woods of identitarianism and culture wars that I critiqued in Lessons from the Counterculture; but for the political right, 2008 presented a massive opportunity. This was their modern Weimar Republic, just like in Germany during the ‘20s and ‘30s, a desperate spiral was driving our political culture inexorably towards rage and fragmentation. The established political class failed to articulate a viable alternative to zombie Capitalism – the spiral turns downwards - Silicon Valley “disruption” expanded its economic vandalism, the Invasion of the Bodysnatchers process – the spiral turns again – this produced even greater economic precarity, social atomisation and political alienation (the emergence of the gig economy is a prime example) – turn - tech companies, and in particular social media platforms, that depended on ever-inflating user numbers, market share, captive audiences and data mining in order to justify the logic of their venture capital investment models exploited all these pathologies for their own ends – turn again, down, towards the void.

During an interview on Yascha Monk’s The Good Fight podcast in January 2025, The economist, and author of Technofeudalism, Yannis Varoufakis, commented on the dialectical nature of the modern relationship between computers, individuals and the tech companies, and what it has meant for human behaviour:

It's produced means of behavioural modification. Now, behavioural modification has always been around. This is not new: every preacher, every author, every politician, every philosopher tries to modify our behaviour. Every psychologist, every advertiser, for that matter, especially since the Second World War. What is new is that this has become automated. It has been given as a task to a machine. And not only that, but it is the most dialectical of machines in the sense that it is a machine that interfaces with you in real time, day and night. So you would take Amazon's Alexa or Siri…or the Google Assistant or any of these devices—essentially, you're training them. You're training Alexa to know you. You're training it to train you to train it better; to give you good advice, capture your trust…and it does give you good advice, whether it is Spotify recommending music, or Alexa recommending books, or what to do on your night out. It gives you good advice and gains your trust. Once it has implanted into your mind a preference for a particular product or service, it actually sells it to you directly, bypassing markets.

Varoufakis’s example neatly illustrates the dialectical endpoint of Douglas Engelbart’s “augmentation” thesis. It describes how humans would adapt, in their personal, individual relationships with computers, to become more easily exploited.

The convergence of the instability and immiseration bred by neoliberalism’s collapse, its reincarnation in zombie form, the Bodysnatcher disruptors, and Silicon Valley’s dopamine-led project to keep people on their devices and engaged, created the ideal conditions for a whole society of Otaku and net-rightists to emerge in the West. Right-wing strategists were quick to spot how the exploitative potential of technology could be harnessed for political ends; Steve Bannon publicly expressed an ambition to tap into the online communities of what he called “rootless white males”, and the tech companies would be more than happy to assist him in doing do so.

Perhaps it’s a coincidence, or perhaps it’s intrinsic to decentralisation, but the “fully distributed internet” would contribute, in the Web 2.0 era, to atomisation, loosening of communal bonds, disintegration of shared cultural experience, and the “epistemological crisis” warned of by Barack Obama in November 2020, two months before armed mobs of right-wing conspiracy theorists, radicalised online, launched an assault on the Capitol. John Perry Barlow’s utopian, “virtual world” generated all these monstrosities precisely because it’s virtual. It’s inhuman, and that inhumanity would naturally produce a virtual, inhuman politics.